Advocates for coalition shared their stories about becoming homeless and how they overcame challenges associated with homelessness.

Homelessness can affect anyone, regardless of their background or socioeconomic status. The important thing is to reach out for help.

“Never be afraid to speak on things that happen,” said Cassandra Staton, one of the three panelists at the Faces of Homelessness panel discussion on Nov. 11. “You have to share your story. Talk to somebody and don’t be afraid to speak.”

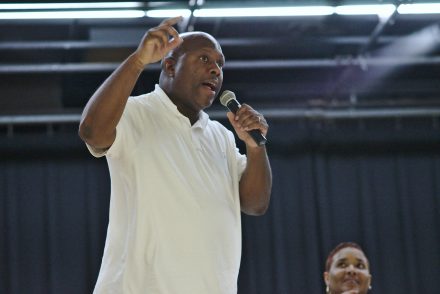

The panel, presented as part of Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week, allowed three panelists to share their life stories and experiences with homelessness to a crowd of hundreds gathered in McKinnon Hall. They painted a picture of how their lives descended into chaos, and how they have been able to climb back up.

“How many of you know someone in your personal life who has experienced homelessness? How many of you know of someone who moved back in with a friend or family member to get over a financial crisis? Now, the only difference in these two situations is that in the first one, the person had someone to fall back on,” Pirtle said.

Although Staton was born into a middle-class family and received a good education, Staton said multiple factors contributed to her becoming homelessness. Along with certain decisions she made, she was molested when she was six years old — a trauma that impacted her for years. “I had my whole innocence taken from me by two family members,” she said. “I suffered in silence.”

She found little help from a mother who suffered from alcoholism, and had her first child at the age of 16. She graduated from high school at 21, but continued to suffer the effects of being molested alone. “I didn’t understand why my mother couldn’t be a mother and why my father couldn’t be a father,” she said.

She would later become addicted to crack, which contributed to the instability in her life. In her 20s, she battled crack addiction and mental illness before becoming homeless and struggling to take care of her two children. “I have taken them to sleep in abandoned buildings, abandoned cars,” she said. “I had abusive men that would put guns to my head to make me do the unthinkable things just to feed my children.”

It was her faith that helped her through hard times. “If I didn’t have a personal relationship with God, I don’t know where I would be today.”

Like Staton, Kelvin Lassiter wasn’t born into homelessness. He grew up in the suburbs of Washington D.C., with his father in the U.S. Navy and his mother working at a local hospital. “We looked to be doing really well on the outside, but on the inside, we weren’t doing so well,” he said.

The problems started when Lassiter’s father was shipped to Vietnam. “The family structure as we knew it started falling apart,” Lassiter said. “When he came back, he was a different man.”

His parents’ relationship suffered from a lack of communications, and other family events including the death of his grandmother, the birth of his sister and his mother getting diagnosed with breast cancer changed the family dynamic forever.

One day, Lassiter’s mother received a call informing her that the mortgage on the house was eight months late and the house was being auctioned. Due to the lack of communication, she knew nothing about this.

Eventually, Lassiter and his family moved out and stayed with relatives. Finding a new apartment was difficult and his mother’s health deteriorated. She passed away when Lassiter was in high school.

Lassiter spiraled into a depressive state and stopped caring about himself. By 22, he stopped going to work and landed on the streets with no sense of direction. He turned to drugs and survived by relying on park benches and soup kitchens. “One day, when I looked up, I was 38 years old,” Lassiter said. “I wasn’t raised like that. It was time to make some change.”

Lassiter took to heart one lesson his mother had left behind. “I knew I could always refer back to the church,” he said. “So that’s what I did.”

The preacher of the church he visited bought a house for men who were trying to get their lives together. The preacher asked Lassiter to do one thing to turn his life around. “He slid one book in front of me,” he said. “It was the Holy Bible.

“My life didn’t change right in that moment, but it did change. From that day forward, Nov. 30, 2002, I’ve been clean and sober ever since,” Lassiter said. “It’s not how you start. It’s how you finish. And you must finish strong.”

David Pirtle lived a lower-middle-class life, never imagining that he would become homeless. He said he didn’t think about homelessness as a circumstance, but rather as a character trait. “I had a decent job. I had a nice apartment,” Pirtle said. “I never thought homelessness could happen to me.”

But in his late 20s, Pirtle started developing symptoms of schizoaffective disorder depressive type, ignoring them until they overwhelmed him. He lost his job and his apartment and began hearing voices and having delusional thoughts. Laws in place in Phoenix, where he was living at that time, criminalized sleeping outdoors and would drive him from the area — first to New York City and then to Washington, D.C.

“The point of these laws is really to drive the homeless community someplace else,” he said.

By now, Pirtle was both mentally and physically sick, and was the victim of multiple attacks while living on the streets. A shoplifting arrest would help turn his life around after a condition of his release was that he seek help at a shelter. He started taking medication and got involved in advocacy, which is how he ended up with the National Coalition for the Homeless.

“What I learned the hard way is the only difference between someone who is homeless and someone who isn’t is that they don’t have a home,” he said.

This event was part of Elon’s Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week and was hosted by the Kernodle Center for Service Learning and Community Engagement, Campus Kitchen and Habitat for Humanity.

“We ultimately wanted to host this event to bring awareness to the Elon community because so many people don’t know much about housing insecurity that happens on the outside, so by bringing in a panel we promoted awareness of this issue as a whole,” Habitat for Humanity student leader Arianna Shahin, said.

Ashlyn Deloughy ’22 contributed to this report.