Why does dementia affect some populations more than others? Life experiences, chronic stressors and lack of health equity may be key to understanding, neuroscientist Indira Turney said during a Voices of Discovery lecture Monday.

Genetics play a role in whether we develop Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, but the sum of our life experiences may have more influence on how our brains age, cognitive neuroscientist Indira Turney said during Monday’s lecture as part of the 2022-23 Elon University Speaker Series, “Living Well in a Changing World.”

Those experiences — chronic stressors, levels of income, access to healthy diets and activity — look different across demographics and may account for why Black Americans are more likely to develop dementia than their White, Hispanic or Asian American counterparts.

“A lot of the reasons people develop dementia are things we can change,” said Turney, an associate research scientist at Columbia University Medical Center. “African Americans have the highest rates of dementia across age groups, as early as 65. Asian Americans have the lowest mean, and White Americans are in the middle. The goal is for everyone to reach the Asian American rate as shown in the research, which would be health equity. To do that, we must first accurately identify the disparities, show they exist and what’s driving them.”

Turney’s presentation, “Weathering and Patterns of Brain Aging by Race and Ethnicity,” outlined data and results from her research involving seniors and their children in New York City neighborhoods. Her appearance in McCrary Theatre was also part of Elon College, the College of Arts and Sciences’ Voices of Discovery speaker series.

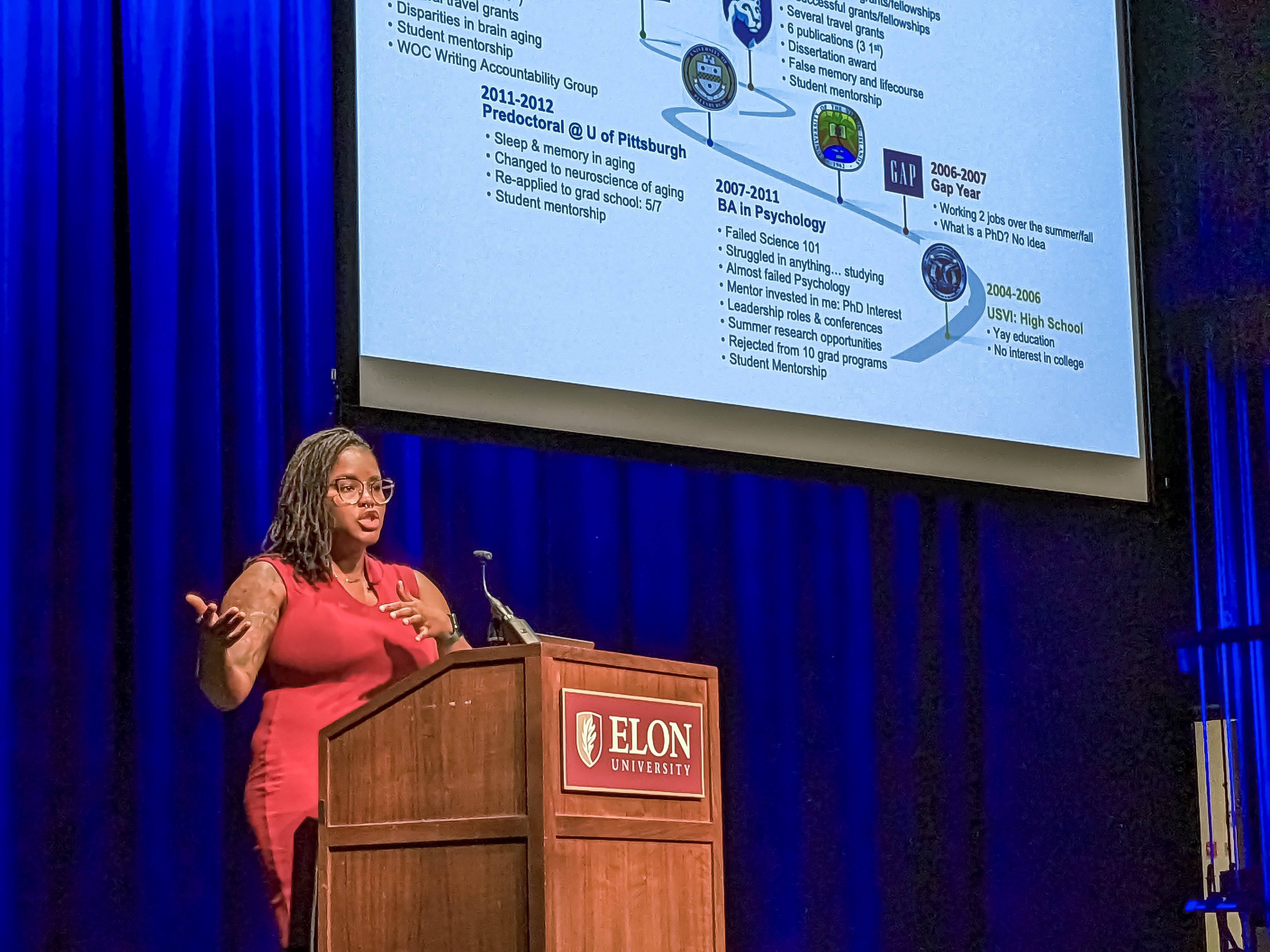

Turney’s expertise is in studying Alzheimer’s disease, dementia and brain aging with a focus on understanding how racism affects the body, brain and health. She earned a doctorate in cognitive neuroscience from Pennsylvania State University and is a postdoctoral fellow at the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain at Columbia University Medical Center. She hopes her work will improve the detection and treatment of Alzheimer’s and related dementias and develop prevention programs to target environmental, socio-cultural and biological mechanisms of change in at-risk populations.

As we age, our brains naturally lose mass and volume, but excessive loss of brain mass and structure is abnormal and may be indicative of dementia. Other signs of cognitive deterioration are white matter hyperintensities, often caused by tiny strokes occurring over time.

Turney’s research has shown that older Black adults have higher rates of white matter hyperintensities compared to White and Hispanic study participants. Even in midlife, Black people have more white matter hyperintensities than other races and ethnicities.

Her research has identified some possible causes of those disparities.

She focused much of the presentation on differences in biological age across race and ethnicity, studied by other researchers and which she uses as a hypothesis to explain her own work. A group of 30-year-olds may have the same chronological age, but the work they do, the conditions they live in and the levels of stress they are under cause “wear and tear” on the body. That can make people’s biological ages differ. For instance, Turney showed research data indicating that 30-year-old Black women have biological ages five to eight years older than their chronological age. Differences between chronological and biological ages in White men and women were “negligible,” she said.

“The cumulative impact of social, physical and economic adversities faced by African Americans leads to early health deterioration and advanced biological aging, which is believed to be caused by chronic or reoccurring stressors,” Turney said.

Another study compared income levels across race and ethnicity with signs of cognitive decline, using New York City’s median annual income of $35,000 as a demarcation. Minorities were more likely to earn less than White residents, overall, and more likely to earn less than the $35,000 threshold. Preliminary data showed that MRIs of middle-aged Black Americans who earned less than that median wage showed greater levels of white matter hyperintensities in their brains.

“There was no relation to income in White individuals. In Hispanic individuals, there was a slight difference, but in Black people making less than $35,000 a year, they were more likely to have greater levels of brain aging,” Turney said. “We need to continue to look at why people with less income are at greater risk for developing dementia. Is it access to healthcare? Are there other underlying health conditions? Is current (income) more important than a family’s income during childhood?

“What I actually found is that (family income during) childhood only matters for White individuals. In Black individuals, midlife income is more important.”

Throughout, Turney emphasized the need for more thorough data collection involving minority populations often underrepresented in studies. People who voluntarily present to a clinic for treatment or research may not represent the populations most affected or at-risk for certain conditions. Those at-risk may not even know their cognitive symptoms are abnormal, chalking them up to the standard effects of aging, she said.

“If we’re looking for a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but we’re not studying the people who are most affected by it, if they’re not included in the study, we’re lacking answers in what’s causing Alzheimer’s,” she said. More thorough and targeted data collection could lead to the development of “precision treatments for all groups of people.”

She ended with a call for the next generation of cognitive neuroscientists to expand the search for the root causes of cognitive decline.

“My focus now is to get a more precise measure on how the body is aging, not just chronological aging, but to find out if life experiences are more important than chronological aging,” Turney said. “We also need to study adolescents and children to see how life experiences affect our genetic makeup to identify different critical timepoints or periods of susceptibility. Hopefully, one of you out there will start to study different generations so we can study causes across different groups of people at different life stages.”