Dewey Hooper '40 went missing in action during World War II, but his history found its way back to Elon's archives in a special online exhibit.

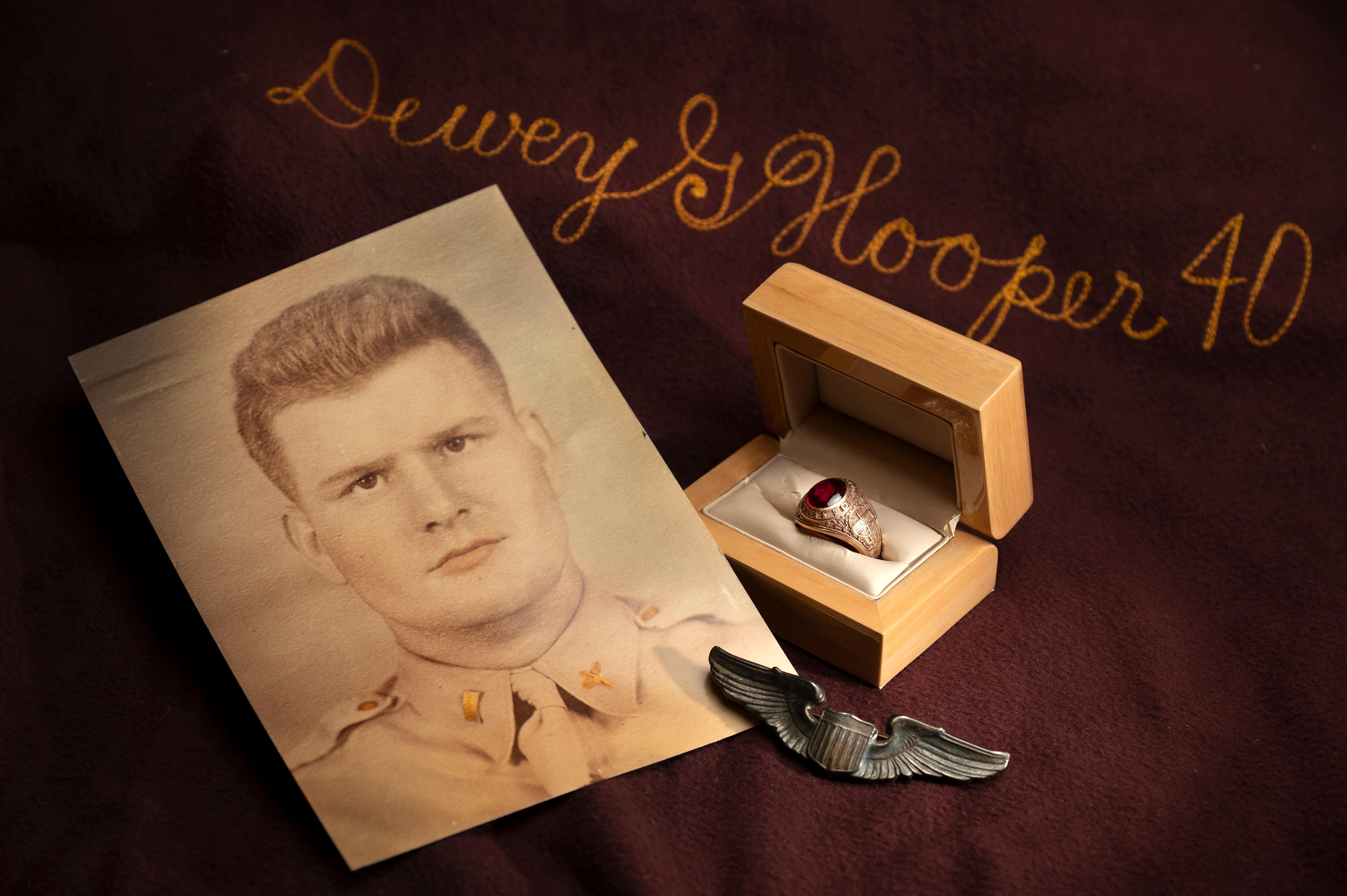

When Dewey Hooper ’40 perished after his plane, “The Texas Terror,” crashed off the coast of Australia in 1942 during a tropical storm, he had a strong reminder of his Elon education with him — his Elon College class ring.

But the ring wouldn’t be discovered in the wreckage on Hinchinbrook Island near Australia’s Great Barrier Reef until nearly 50 years after Hooper and his crew went down. As luck would have it, it was spotted and retrieved by an Australian man as he explored the crash site in 1990, with the ring returned to Hooper’s family the following year and later donated to the university.

The ring’s return is just one miraculous part of the story of Dewey Glenn Hooper, now detailed in a new online exhibit that documents his life as an Alamance County native, Elon student, young schoolteacher and eventually a World War II pilot.

The exhibit, titled “He Knew the Dangers Before Him: Elon Graduate Dewey Hooper in World War II,” was curated by Archivist and Assistant Librarian Randall Bowman and includes artifacts from Hooper’s life that were given to the university by Hooper’s family, including his Elon class ring. Among the items on display in the digital exhibit are his second lieutenant bars and flight wings, portions of his aircraft and items from when he was a student at Elon.

Bowman became aware of Hooper’s story while doing research for an exhibit about Elon College during World War II. It made such an impact on him that he decided to focus the exhibit on Hooper. “I came across this collection and the story of Dewey Hooper, and I just became fascinated by it,” Bowman says.

THE MAN

Born Feb. 22, 1919, Hooper was the eighth of 10 children who grew up on the Hooper family farm in Alamance County close to Mebane. He began his college education at what is now N.C. State University in Raleigh, where he was a member of ROTC, but after two years transferred to Elon College.

At Elon, he was a member of the Psi Nu Fraternity while also serving as the movie projectionist and a photographer. He was focused on becoming a teacher, and he graduated in 1940 with a bachelor’s degree and received his high school teaching certificate to teach math and science.

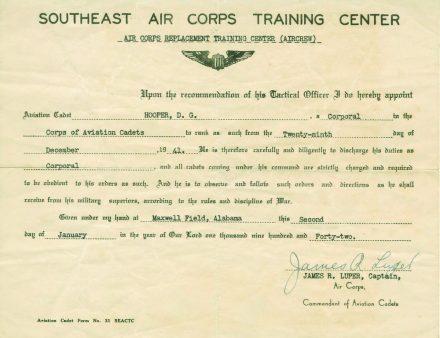

After teaching algebra, chemistry and physics in high school for a year, Hooper volunteered for the U.S. Army in May 1941, not knowing that the country would be thrust into a world war a little more than six months later. He eventually landed in the Air Corps and completed his pilot training at Turner Field in Albany, Georgia, during the summer of 1942. Among the items in the collection is a flight logbook detailing his training at various air bases as he learned to fly.

He earned his wings just a little more than a year after leaving the high-school classroom in Elizabeth City, North Carolina, where he taught. “In 1942, we didn’t know if we were going to win the war,” Bowman says. “Things were dire, and young men like Dewey Hooper got thrown into it.”

By November 1942, Hooper was halfway around the world, stationed at the “Iron Range” airfield in Queensland in Australia, which was described as “a dusty red scar gouged in the rainforest.” Hooper was a co-pilot of The Texas Terror, a B-24 Liberator that could carry a crew of up to 10.

THE MISSION

On the morning of Dec. 18, Hooper took off on a non-combat mission, picking up seven passengers at a Royal Australian Air Force airfield in Garbutt and then beginning the return to the Iron Range. The Texas Terror would never arrive. A heavy tropical storm would blow Hooper and his crew off course and cause them to crash near the summit of Mount Straloch on Hinchinbrook Island in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. The five crew and seven passengers on the B-24 Liberator were killed.

Hooper was 23 years old.

Due to the location of the crash, the wreckage wasn’t found until 1943. Bowman explains that the face of the mountain is incredibly steep, with at times a 50-degree incline, and is virtually unscalable. Photos of the mountain included in the exhibit speak to the impenetrable nature of the rainforest and the steep terrain that foiled search efforts for years. Hooper’s remains were recovered and interred in Australia after the war, but were not returned to the United States for burial until 1949.

On the morning of Dec. 18, Hooper took off on a non-combat mission, picking up seven passengers at a Royal Australian Air Force airfield in Garbutt and then beginning the return to the Iron Range. The Texas Terror would never arrive.

Miraculously, an Australian man named Ron Deering who was living in Texas at the time made the trek to explore the wreckage in 1990. Deering documented his journey well, with the online exhibit showing photos he took of the crash site, now largely overgrown, and the wreckage of the plane. But twisted metal from the fuselage and cockpit parts weren’t all that Deering found.

“He was exploring the wreckage and looked down and saw a glint of gold,” Bowman says. “He had found Dewey’s ring.”

That started Deering’s quest to reunite the ring with the family of the late airman. Through Elon, he was able to connect with Hooper’s family. Deering returned the ring and other items to them the following year, with those items and others later given to the university along with photographs and documents about Hooper. “He could have kept the ring and done nothing with it, but he went out of his way to connect with Elon and find Dewey’s family,” Bowman says.

THE SACRIFICE

The online exhibit also shares details and photos about other efforts to honor those who perished in The Texas Terror crash. In 1959, a cadet branch of the Royal Australian Air Force decided to place a memorial at the crash site. An aluminum cross fabricated from aircraft parts at RAAF Garbutt with a brass plaque bearing the names of the 12 victims now sits on a cliff by the wreckage, nicknamed “The Cross in the Clouds.” A memorial including one of the propeller blades from The Texas Terror was also erected in Ingham, Queensland, close to Hinchinbrook Island and Mount Straloch.

The items recovered by Deering and given to Hooper’s family combine with other items from Hooper’s time at Elon to paint the picture of a life cut too short, and of a man willing to serve his country during a critical and anxious time in this country’s history. Through the online exhibit, visitors can learn about not just Hooper’s life, but life as an Elon student during the pre-war period as well as life as a U.S. Army airman in the early years of World War II.

“The whole thing is a great story,” Bowman says. “When I found this collection and started to read through it, I knew I wanted to put it into an online format where a lot of people could access it and see the whole story in a narrative form.”