- Home

- Academics

- First-Year Writing

- Phoenix Rhetorix

- 2021-2022 Journal

- Not Just My Story: Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault in Schools by Izzy Jacobs

Not Just My Story: Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault in Schools by Izzy Jacobs

Not Just My Story:

Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault in Schools

A Feature Article by Izzy Jacobs

The American Association of University Women (AAUW) states that more than 80% of people become victims of sexual harassment before they finish high school, and most often, their perpetrators are their peers.

I am a part of that 80%.

In my eighth-grade French class, I sat behind someone who would sexually harass and assault me every day. He would make comments about my clothes and how my body looked, suggest provocative things, grope my body, and encroach on my personal space. The worst part is that we sat directly in front of the teacher’s desk, and yet nothing was done to stop this abuse.

Sexual misconduct in schools, and other stories like mine, are not as rare as many people believe them to be. Over 13,000 students in the United States experience sexual assault or rape and are forced to face the effects of others’ actions on their health (Civil Rights Data Collection).

To begin, it’s crucial to define terms properly and specifically. Sexual harassment is defined by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.” The Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) defines sexual assault as “sexual contact or behavior that occurs without explicit consent of the victim.” Sexual misconduct and sexual violence are general umbrella terms that encompass any form of unwelcome harassment and assault. It’s important to identify these terms because they give us the language to speak about sexual violence concretely and accurately.

Rachel E. Gartner and Paul R. Sterzing, from the University of California, Berkeley, state that in the long-term, victims of sexual harassment are more susceptible to negative health outcomes like an “elevated risk of self-harm, suicidal thoughts, maladaptive dieting, substance use, and feeling unsafe at school” (Gartner and Sterzing 494). Nevertheless, students continue to get violated in classrooms and hallways.

For years, students have been suffering from sexual harassment and assault in middle, high, and even elementary schools, but the action that has been taken on the part of education systems to stop it has not been enough. Despite its prevalence and the scars it leaves on its victims, sexual harassment and assault continue to remain unaddressed.

School, a Place Lacking its Most Basic Value: Education

I went to school in an environment that forcefully imposed dress codes upon students. However, they did not educate their students on sexual misconduct in any aspect of what constitutes sexual harassment and sexual assault, what steps to take when one experiences sexual violence, and what rights each person is entitled to as a human being.

As a 14-year-old with no knowledge of sexual assault in the slightest, it never occurred just how wrong my perpetrator’s actions were. There was always an uncomfortable feeling that loomed inside me, but I convinced myself that what he was doing was normal and okay. Without the proper information, I didn’t know that it was my right to say no and to tell him to stop. I was never taught how to handle situations like that, or what actions to take with the school, and I certainly wasn’t taught how to cope with the trauma or offered any kind of help from the school. It wasn’t until I reached high school and started educating myself that I realized what had happened to me.

And I’m not alone in my experiences.

The Sex Education Forum surveyed 2,000 11- to 25-year-olds and discovered from their research that 50% of respondents were not taught in primary school how to go about getting help if they were sexually assaulted. Thirty-four percent of those surveyed were not taught anything in school about consent; seventeen percent hadn’t learned that people’s genitals are private and should not be subject to unwanted sexual advances.

If schools were to implement educational programming on sexual health and violence, then perhaps the number of students who withstand these horrors would decrease and there would be fewer victims who struggle in the aftermath. Perhaps if my middle school offered sexual harassment and assault educational resources, I wouldn’t have to participate in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to help me process the trauma that I’ve carried with me since middle school.

Perhaps that would be a start.

Trauma is the New Normal

Sexual harassment and sexual assault have become so normalized that sometimes kids feel it isn’t worth doing anything about what they have experienced.

I can attest firsthand that sexist comments, a form of sexual harassment itself (EEOC), were something that one often heard just walking through the hall or listening in on a conversation between a group of boys. In Kingsway Middle School, girls were often the butt of the joke, objects meant for boys’ entertainment. Yet, there wasn’t even one instance where I saw an adult in a position of authority step in to stop that way of thinking.

People may think that sexist jokes are harmless and just “for fun,” but they carry a lot of weight. In the short-term, victims of these jokes –– most often girls –– form a negative self-image and lose confidence in themselves. On a larger scale, the normalization of these comments and stereotypes perpetuates the detrimental cycle of thinking that allows these thought processes to occur in the first place. These seemingly harmless microaggressions are a major contributor to how sexism and gender-based violence have managed to thrive.

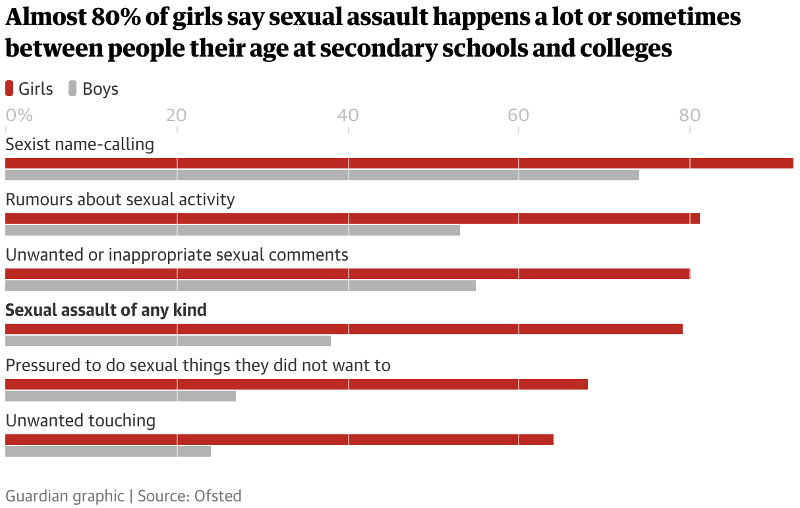

The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) surveyed students in the United Kingdom and found that 92% of girls and 75% of boys responded that they experienced recurrent sexist name-calling in school (Weale). As seen in the chart below, sexual rumors are also highly reported by students surveyed in the Ofsted Report. In their research on sexual violence and gender-based microaggressions, Gartner and Sterzing have discovered that “the spreading of sexual rumors . . . is consistently reported as the most upsetting” (Gartner and Sterzing 494). One student interviewed by the House of Commons stated, “You see it every day in my school. I wouldn’t say it was appropriate, but it still happens” (House of Commons).

Sally Weale, “Sexual harassment is a routine part of life, schoolchildren tell Ofsted” (Weale)

When I told my mom about my experiences, she asked me why I never spoke up. “Because they wouldn’t do anything.” That was my answer, and I stand by that to this day. Until we start seeing changes in schools, victims will continue to suffer in hopeless silence.

Just because victims are not speaking up doesn’t mean that this isn’t happening.

The Impact of Sexual Misconduct on School Safety

When parents send their kids off to school every day, they expect that the school’s policies and administrators will keep their children safe. My parents waved me off to school expecting me to learn in a safe environment.

But soon enough, the days when he didn’t assault me were more surprising to me than the ones that he did.

This classmate was the reason I spent my days focusing not on learning in classes throughout the day but anticipating what the harasser would do to me in French class.

In their research, Gartner and Sterzing found that “victims of sexual harassment react[ed] to their victimization by avoiding the person who bothered or harassed them (40%), talking less in class (24%), not wanting to go to school (22%), changing their seat in class (21%), and experiencing difficulties paying attention in school (20%)” (Gartner and Sterzing 494).

Many people would agree that a safe environment where every student feels respected is the best place for students to learn. What many fail to acknowledge is that the very presence of sexual violence shatters that possibility. As the AAUW observed, students who are victims of sexual harassment become less motivated and focused while they are in school (AAUW).

The United Kingdom’s House of Commons came to a similar conclusion from their findings with the Association of Teachers and Lecturers. Their surveys of teachers concluded that girls faded into the background as a result of being sexually harassed in school. They became even less likely to participate in class activities, take academic risks, or do anything to make themselves stand out (House of Commons).

What Does Change Look Like?

As a result of the Ofsted Report, the Department for Education in the UK has promised to provide more support for schools to combat the issues of sexual harassment and sexual assault. One action taken by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was to set up a helpline in April 2021 “to support children reporting abuse in education”; and in two months, the helpline received 426 calls and “80 referrals [were] made to external agencies including police and social services” (Weale).

In addition, Ofsted suggested that headteachers, the British equivalent of administrators, take a “whole-school approach.” This includes running sufficient health and sex education programs that address all forms of sexual harassment, and thoroughly covering consent and the sharing of “explicit photos” (Weale).

In the United States, The Blue Bench is an example of an organization that is taking major strides toward making schools free from sexual assault. The Blue Bench is a nonprofit based in Denver, Colorado and uses the motto “Ending sexual assault through prevention & care.” They work to change the conversation around sexual violence, provide support, advocate for survivors and their loved ones, and implement preventive care in their community.

Tackling a problem as deep-rooted as sexual violence is daunting. This is why we need to look at the little things we can do to start the process. Having organizations like The Blue Bench and helplines such as the NSPCC are steps in the right direction. It starts community by community, conversation by conversation.

We need to start asking questions.

How do we start implementing sexual awareness education in schools with younger kids? What are the challenges present in doing that, and how do we conquer those challenges? How do we support teachers and school administrators in this process? How do we best support survivors?

All of these are difficult questions that we may not have the answers to, but change must start somewhere and asking questions is a good place to begin. We also need to bring survivors to the forefront and provide a safe and encouraging environment for all people to share their stories, as I have in this essay. Individual voices are important because everyone needs to understand that it’s not just my story.

References

AAUW. “Crossing the Line: Sexual Harassment at School.” AAUW, 2 Apr. 2020, www.aauw.org/resources/research/crossing-the-line-sexual-harassment-at-school/.

Civil Rights Data Collection. “Number of School Offenses by Type, by State: School Year 2017-18.” Civil Rights Data Collection, https://elonuniversity-my.sharepoint.com/:x:/g/personal/ijacobs5_elon_edu/ER_ELe0myM5NsKYYTIdpS1kBNW-_CpUMdlBYLC1AAoEaBw?rtime=L9UK0ku72kg.

Civil Rights Data Collection. “ORC Data.” Civil Rights Data Collection, https://ocrdata.ed.gov/estimations/2017-2018.

EEOC. “Sexual Harassment.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, www.eeoc.gov/sexual-harassment.

Gartner, Rachel E., and Paul R. Sterzing. “Gender Microaggressions as a Gateway to Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault: Expanding the Conceptualization of Youth Sexual Violence.” Affilia, vol. 31, no. 4, 27 June 2016, pp. 491–503., doi:10.1177/0886109916654732.

“Home.” The Blue Bench, https://thebluebench.org/welcome.html.

House of Commons. “The Scale and Impact of Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence in Schools.” House of Commons, Parliament UK, 8 Sept. 2016, publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmwomeq/91/9105.htm#footnote-172.

“Ofsted.” GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ofsted.

RAINN. “Sexual Assault.” RAINN, https://www.rainn.org/articles/sexual-assault.

Weale, Sally. “Sexual Harassment Is a Routine Part of Life, Schoolchildren Tell Ofsted.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 9 June 2021, www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jun/10/sexual-harassment-is-a-routine-part-of-life-schoolchildren-tell-ofsted.

Author Interview – Izzy Jacobs

Q: Please introduce yourself: What is your preferred name, pronouns, and major(s)/minor(s)?

A: My name is Izzy Jacobs and I use she/her pronouns. I am a sophomore, with a double major in French and Cinema and Television Arts (B.F.A.), and a minor in Human Resources.

Q: What inspired you to write about sexual harassment and sexual assault?

A: My past experiences with sexual assault changed my life. I’ve carried the pain and trauma with me every day since middle school, often with silence. I found that no one, in or outside of school, talked about sexual abuse. I felt alone and stayed silent for years. It wasn’t until high school that I taught myself about everything related to sexual violence: what it is, consent, its effects on victims, and trauma treatments. I became immersed in advocacy for education surrounding sexual violence and wanted to make people aware of the prevalence of this issue. I wrote this essay to shed light on the issue of schools not acting against sexual misconduct, and for readers to hear the story of someone who had a first-hand experience with assault in school. It’s important to me that people realize how harmful sexual violence, on all levels, is and what we can do to help victims.

Q: What would you like Phoenix Rhetorix readers to remember about your piece after [reading/watching/listening] to it?

A: After reading my piece, I want readers to feel inspired and motivated to make a change. I want them to remember that sexual violence is an issue that hurts many people. It is still very prevalent today and just because it isn’t being talked about, doesn’t mean it isn’t happening. I would like readers to be aware of what can be done. Both on an individual level and in bigger communities, and to raise awareness to end sexual violence.

Q: How do you see your piece contributing to Elon’s ongoing conversations regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion?

A: I wrote this paper to spread awareness about the topic of sexual violence. I think that that is going to be the main contribution to Elon’s focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Since many survivors stay silent, we often don’t know that there is a community of support within each other. I hope that sharing my story will resonate with others who have similar experiences and that Elon will be encouraged to take strides to protect survivors; whether they are struggling or not. There is always more to be done and every person deserves to be included in their community.

Q: What writing and/or research skills did you develop in completing this piece?

A: Though I had a lot of education and experience with writing before college, my ENG 1100 class allowed me to improve my weaknesses in my writing. Through the work and collaboration that I did in that class, I am more cognizant of long, wordy sentences and paragraphs. In addition, I learned the importance of making sure that all of the evidence and outside sources used in essays must back up my thesis and strengthen my arguments. I was able to make the most improvement on argumentative essays and was taught how to add touches of personality into each piece of professional writing that I do.

Q: What advice would you give to students who are currently enrolled in ENG 1100, might want to complete a similar project, or are interested in publishing in Phoenix Rhetorix?

A: My biggest piece of advice for students enrolled in ENG 1100 is to get involved and actively participate in and out of class. I got the most out of that class by being an active learner in the classroom and putting my best effort into the writing that I did. I took each assignment to heart and used them to share pieces about my life and my interests. I made sure to add my own personal touch to the writing that I was doing.

As for someone who may want to complete a similar project or get published in Phoenix Rhetorix, my first piece of advice is to make good connections with professors in the English department. Not only can they help you submit to the writing contest, but they will be with you throughout the writing process to advise you on your work. Another piece of advice is to go into a project or writing contest with everything you have. Use the strongest writing possible with as much personality and uniqueness as you can. If you work hard, strive for a result, and continually work to improve your work, you’ll have something to show for it.

ENG1100 Faculty Interview – Julia Bleakney

Q: During your ENG 1100 class, what about Izzy’s piece stood out to you?

A: Every student in my ENG1100 class was working on a fascinating topic, but Izzy’s piece stood out because she was so personally committed to the topic. Izzy had been thinking about sexual abuse and sexual assault in high schools since she herself was a high school student, and she’d had previous opportunities to speak to high school audiences about the topic. Izzy was laser-focused on the purpose of her piece and what she wanted it to accomplish.

Q: How did this piece evolve as Izzy completed this course assignment?

A: The biggest evolution in Izzy’s piece was the choice of genre. She decided that it would be more impactful if she switched the genre from a traditional essay into a more journalistic style of writing, which she felt could be written in a more accessible tone and therefore more likely to reach her intended audience. Izzy wrote this paper for a research assignment, and the class was then asked to “remix” the research into another genre for a new audience. So, another evolution occurred when Izzy remixed the journalistic article into a research poster presentation that she might present to a group of high school teachers and administrators. As her piece evolved through different genres, Izzy was able to solidify her central claims, most compelling evidence, and strong voice.

Q: Did Izzy face any particular challenges with this assignment? If so, how did you help them navigate those challenges, and/or how did they work to overcome them?

A: The challenges Izzy faced were also related to developing a writing style appropriate to the journalistic genre, especially as she had already started to write the paper in one genre before she decided to switch to a different genre. Izzy and I met to talk about which information to include and exclude and how to reorganize the piece so it would foreground the most important claims she wanted to make. There was a moment when Izzy felt unsure about her ability to write the journalistic piece, but with a solid plan and a bit of distance between the first and second draft, she was able to achieve the revision she wanted.

Q: What was the most rewarding part of working with Izzy on this project?

A: Because Izzy cared so much about the topic and about a real audience for her work, our conversations were always lively. It was rewarding to help Izzy harness her passion into a focused and powerful paper.

Q: What advice would you give to students who are currently enrolled in ENG 1100, might want to complete a similar project, or are interested in publishing in Phoenix Rhetorix?

A: First, select a topic to write about that is important to you and then select an authentic venue and audience for your writing. Some students coming into college perhaps don’t realize that their writing can have power and influence, but imagining a real audience for your work can help your writing come alive. Second, embrace the revision process by sharing your work and your ideas. Revising isn’t just about editing words on the page. Talking through your ideas can clarify your thinking, so talk to whomever will listen—your peers in class, your professor, your roommates, or consultants in The Writing Center. Finally, don’t be afraid to take a risk with your writing, even if it means “going back to the drawing board” half-way through the process, as Izzy did. You’ll be more satisfied with and proud of your work.