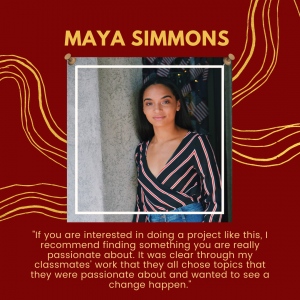

Diversifying Dance Education and Dismantling Existing Biases by Maya Simmons

Diversifying Dance Education and Dismantling Existing Biases

A Research Essay by Maya Simmons

When I decided I wanted to go to college to earn a BFA or BA in Dance, I spent that entire summer doing research on all the options for schools I could go to. Only, I was having trouble, because I knew I wanted to be able to do jazz, hip-hop, and African styles. It seemed like every school I looked up to check their website had none of those available at first glance. Instead, they were a top Ballet or Modern university/conservatory where you could choose a Ballet or Modern focus. Where were the rest? I wanted to be able to do ballet, yes, but I also wanted the opportunity to be able to find creative release through other styles. My mom and I discussed, and we knew I would have to make the best decision for myself. However, I knew that decision would require me to settle on a school that might offer those things but only as electives. Why should I have had to make that tough decision? Dancers of color should be allowed to not feel as though we are being limited in our expression because our cultures are being put to the side. Dance is an art form that celebrates different cultures in a beautiful way and our education systems must do the same.

Dance is a reputable art form that has consistently brought beauty and entertainment to the world, but scholars and dance community members are finding there is a lack of diversity in the education and performance of varying styles. The marginalization of certain dance styles has made them overlooked, which maintains negative ideals and critical assumptions about them. Dance education has certain pre-conceived norms about which styles of dance are “more acceptable” than others. The dominant norm is Eurocentric dance forms that exclude forms that are significant to other cultures. Educators and interested students find that dance forms like West African, Salsa, and Hip-Hop are not as readily available in US universities as Eurocentric forms like Ballet and Modern. These dance styles are seen as “electives” in many studios and schools, while ballet and modern have levels to progress in and high-quality training. The neglect of dance education and pedagogy has let misinformation seep into many university programs all over the country. There are long-standing ideals that plague how dancers in these programs should learn about dance to become well-rounded and successful. The absence of diversity in dance is undeniable and harmful.

In the United States, racism was more prominent in the early to mid-20th century, but it is still present in the form of implicit bias through microaggressions, hurtful stereotyping, and lack of education and opportunities. Understanding the history of this hurtful bias in the dance world is very important in moving to change it. As an African American scholar invested in dance education and a member of the dance community, I would like to use my knowledge to express how harmful having such an uneven value system is. It is something that students (and even teachers) throughout the country experience. The following synthesis essay provides background information as to how racial bias in the education field has a long history in the dance world, examines its effect on current dancers and teachers, and proposes actions that leaders and dancers in our society can take to change it.

The manifestation of centuries-long prejudice and White supremacy in the world of dance was recognized as early as the 20th century. The lack of awareness and education that plagues dance is not just external, it happens on the inside as well. From my own findings and experience, there is not much coverage on this subject. Because of the lack of coverage, there has been a decrease in progress in diversifying dance programs. Minnesota State University dance professor Julie A. Kerr-Berry uses research evidence from Doug Risner that emphasizes low diversity: “overall ethnicity in undergraduate dance programs indicates African-American participation at only 10 percent, compared to white participation at 72 percent” and “Longitudinal data over the past four years shows that dance faculty are becoming increasingly more white (80% in 2007, up from 76% in 2003)” (50). Fewer African American dancers want to go into higher education for dance, but this is not necessarily a conscious choice. Kerr-Berry corroborates this by stating, “Some African Americans might resist pursuing dance in higher education because of our racist past.” There is, however, a name for this phenomenon. Tracey Owens Patton (Director of African American & Diaspora Studies and Associate Professor of the Department of Communication & Journalism at The University of Wyoming) explains this phenomenon is known as racial tracking. In short, Black and Latinx students are encouraged to go on a “vocational track,” while White and Asian American students get to continue ballet on a “college prep track” (114). Racial tracking has a deep-rooted history based in segregation that continues to affect dancers even in the current decade. Patton describes the implications of this: “This racial tracking in dance perpetuates the myth that ballet is all White, that ethnic minority dancers are not interested or talented enough to perform ballet, and that the ethnic minority body is just too different to be normalized into ballet” (114). This highlights why there have been fewer dancers of color pursuing higher education in dance, as it has been discouraged from the beginning. The discouragement that dancers of color face from early on makes it easier for leaders to be able to perpetuate Eurocentric dance as the most important. As a woman of color who used to dance, Patton’s personal experience solidifies and supports Kerr-Berry’s research. There is a real issue stemming from higher education for dance. What can we do to make sure the problem does not grow like weeds? Or how do we make sure it does not grow more than it already has?

Change begins with being educated and knowing the history of a topic. I argue that leaders have the most power in this situation, as they must put in the work to bring diversity to different programs and companies in the community. If there was any dance pioneer to mention in trying to bring diversity into the world of dance, it would be Alvin Ailey. Thomas F. Defrantz, who specializes in African Diaspora aesthetics and is currently a Professor of Dance at Duke University, describes Ailey as a “committed integrationist” who called for “the need to change in the existing order.” Ailey used his work and company to make sure his dancers and audience members were educated in all aspects of dance, especially the long history of discourse in the African American dance community. Ailey also “continuously spoke out for increased opportunities for African Americans in dance” and worked to expand the “technical, thematic, and musical range of materials available to black dancers” (Defrantz). Ailey fought to make these changes in the 1960s, so the real question becomes how has this translated into the current world? Zita Allen, the first African American critic for Dance Magazine and current dance writer for New York Amsterdam News, wrote a piece following the murder of George Floyd. If there were any time to talk about racism and racial bias found in dance, it would be when everybody began rethinking the narrative and looking for a change. In this piece, Allen drew on quotes from dance pioneers like Misty Copeland and Joan Myers Brown. Copeland expressed that “in the world of ballet, many companies have chosen to exclude Black and Brown bodies and are ‘hiding behind the intended consequences of the systems designed to limit people of color’s access to things like funding, exposure, training and equipment to justify this exclusion” (Allen). Later in the piece, which brings up a very important question, Joan Myers Brown wonders why we are still having this conversation and why we are “‘talking about the same things that should have changed years ago?’” (Allen). Allen is hoping that these conversations will continue to happen and there will be serious changes, like dance companies being held accountable for their actions that have affected dancers of color throughout the country.

As someone who has been moving through the dance community for about a decade, I can affirm that the systems that have been created by Eurocentric educators in the art form are problematic. Higher education settings like universities and professional dance academies have continued to let biases and microaggressions fly under the radar, which allows them to flourish. I have found that Assistant Professor in Theatre and Dance at Austin Peay State University Ayo Walker acknowledges these issues by giving the background, history, current information, and possible solutions. Walker emphasizes this is not something that just appeared in the world of dance: “The development of new dance esthetics by White women and men followed the same system of racial hierarchy and segregation; therefore, they did not view the social dance movements of Blacks as equivalent to their social dance movements” (162). Walker’s background information on how “racial hierarchy” and segregation subconsciously (or consciously for some) seeped its way into current dance education is emphasized in different programs, as ‘White’ dance forms like Ballet and Modern are normalized in curriculum requirements while ‘cultural’ dance forms like West African and Salsa are seen as electives. Walker maintains this when she writes, “Eurocentric concert dance is commonly stressed more than any other style or technique, and other approaches assume a minor role within the curriculum.” The minor role that the styles have taken on is detrimental to dancers of color and their feeling of acceptance in these programs. Professional dance company member and podcast creator J. Bouey emphasizes this but in a more straightforward and radical way. While he and Walker have the same ideas about the implications of the lack of diversity in higher education, Bouey decides to call out the entire dance industry. He takes it as far as to say this practice is “White supremacy in dance” and “White culture is also about theft, pillaging and appropriating.” While these thoughts are on the extreme end of the spectrum, they are not far-fetched in any way. There have been many artists of color that have never gotten the correct recognition and rightful credit for their creations. Instead, it is given to White dance pioneers like Ruth St. Denis, George Balanchine, and Twyla Tharp.

There is an alternate way to look at dance education’s issues with inclusivity and diversity. Many of these issues come from leadership in the field of dance. Robin Prichard (professor in the department of dance at the University of Akron) acknowledges there must be some ignorance as to how to approach the issues. Dance industry leaders are taking on a “color-blind” view by not acknowledging race in their dance spaces. This view, however, can have many implications and cause a lot of problems. Prichard emphasizes educators are not willing to acknowledge their White privilege, but “will have to do the difficult work of giving up the special status given to ballet and modern dance” (172). Ballet and modern are always seen as the most imperative to learn, and educators must take a certain amount of personal accountability for those forms to not have so much hold in dance education. We know there are many reasons for the lack of inclusivity in the dance industry, so why has there not been any true progress in fixing this issue? My own view is that those in the dance industry have stagnant views about dance education.

Recently, there have been contesting ideas about dance education and whether its racial bias is due to the overall ignorance of White dance leaders or systemic White supremacy that most White people in the industry are not aware of. Prichard presents the different options, prompting an important discussion about the differences between the issues. On the one hand, some argue that there needs to be a higher level of self-awareness to White dance leaders’ unconscious biases. From this perspective, the issue of bias can be tackled from the roots, starting with people in powerful positions. On the other hand, some argue that ignorance and subconscious thoughts stem from White supremacy. In the words of Bouey, one of this view’s main proponents, “White culture defines what is considered normal… When the word ‘technique’ is used to talk about a dancer’s grasp of ballet vernacular, we have placed it into the norm; into white dance.” According to this view, dancers and dance leaders have been conditioned to think of Eurocentric dance styles like Ballet as the norm, while other dance styles are seen as deviant. In sum, then, the issue is whether racial bias in dance stems from White supremacy from all dancers and dance leaders or if said dance leaders are taking on color-blind antics that further their ignorance. My own view is that racial bias in dance education has stemmed from a long line of ignorant actions without consequences from both dance students and teachers. Though I concede that White supremacy is one way to describe the ignorance in the situation, I still maintain it is quite a radical view to take. For example, there is a claim that White supremacy exists when BFA or MFA programs only require ballet and modern to graduate instead of other electives. While that can be true because it has existed for so long, it could be argued that because it has existed for so long it has just become the normal thing to do. The fact that the current curriculum is considered normal has let the questionable actions persist for so long.

While Kerr-Berry’s and Prichard’s research provides dim results that do not yield much hope, I believe there are many solutions, as long as leaders, educators, and even students put in the effort. Many different companies and individual dancers have taken on ways to address race and educate others. Brian Schaefer (a journalist/writer who covers many topics from arts and culture) provides evidence that Black bodies used dance as an outlet to educate. Schaefer explains, “Whether in the past or today, addressing this contentious national issue can be a creatively daunting task. But transposing the anger, pain, and sadness of the outside world onto the body, and then onto the stage, is a burden that dance has embraced.” However, that was 2016, and there need to be new solutions that are more about others acting instead of just watching. How can higher education in dance accomplish this? Jessica Giles, a former dancer and current senior journalism major at the University of Florida, provided her take on what steps can be taken. Giles tells White teachers and dancers to “Be a Better Advocate” by breaking the bystander effect (witnessing racism and doing something about it), listening by learning about bias and racism, casting dancers of color, and making advocacy a habit, not a hashtag (as these issues eventually just turn into trends and performance activism). These are simple solutions to a larger problem. Walker provides hard solutions that will take a lot of work. Walker prefaces the solutions with:

Dance students and faculties, as well as administrators, need to substantively engage the importance and necessity for implementing Entercultural Engaged Pedagogy as a blueprint for a more inclusive educational model. Fortunately, there is a growing movement to achieve this end; included in this crusade are the cadre of anti-racist educators mentioned throughout this text. Still, decolonization of the mind is far too complex; this undoing must be unyielding.

I would like to emphasize the statement “decolonization of the mind is far too complex” because it holds a deeper meaning that people will have to take the time to learn. The world of dance needs to start a change somewhere and educating its up-and-coming dancers is the perfect way to begin. I contend that there needs to be real action taken to create change. Right now, any movements that are happening have been treated as a trend instead of something that affects a group of marginalized people. Along with that, there has been a lack of listening. In my experience, if a person of color expresses something that makes them uncomfortable or shows they experienced discrimination, there is an immediate reaction of defensiveness. The disappointing patterns are only going to get worse if the dance community does not come together to make some changes.

A question may stand for some people, and that is why does any of this even matter? It matters because there are dancers and scholars out there who have experienced this never-ending pattern of oppression and marginalization. Because dance education in higher institutions has constantly flown under the radar, the bias continues to grow and block out dancers of color from being able to pursue what they love. While the claims of White supremacy in the dance community are valid, they are not fair in an art form that has only known one thing since its beginning. The bias has become systematic, and there is not an individual who can be blamed for what has happened. All that can be done now is to make progress. I did not realize how prevalent the issue is, but when I sat down to think about it, I noticed my dance classes throughout the past ten years of my life have had that same pattern, making it a systemic issue. The change may not come easily, in fact, it may be something that takes years to develop. However, it can happen if we begin a well-rounded and proper education for our dancers. To begin some change myself, I would like to at least start in my program by presenting different ideas to the leaders to get the ball rolling. The ideas include bringing in more professors of color and granting them tenure, including different styles of dance other than modern and ballet in performances (instead of the Black History Month performance being the only cultural dance program), and getting African classes past the point of an elective. Based on the changes already being made in the program, I am confident that my ideas will be listened to, which is a great first step. After the progress has been made here, I would love to take it further in the future to benefit the entire performing arts community. The current education system lacks diversity and inclusivity by making Western dance forms the most important. However, meaningful dance education is inclusive of everything, and should combine western and non-western dance forms to prioritize diversity and equity for all.

Works Cited

Allen, Zita. “‘Black Hearts Are Burning’ Discusses Systematic Racism in Dance.” New York Amsterdam News, 25 June 2020.

Bouey, J. “Are College Dance Curriculums Too White?” Dance Magazine, 20 Apr. 2020, www.dancemagazine.com/are-college-curriculums-too-white-2645575057.html

Defrantz, Thomas F. Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture. Oxford; New York, Oxford University Press, Cop, 2006.

Giles, Jessica. “Ending Racism on Campus: Like the Rest of the World, Higher Education Dance Programs Have a Long Way to Go.” Dance Magazine, 21 Apr. 2021.

Kerr-Berry, Julie A. “Dance Education in an Era of Racial Backlash: Moving Forward as We Step Backwards.” Journal of Dance Education, vol. 12, no. 2, 16 May 2012, pp. 48–53, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15290824.2011.653735, 10.1080/15290824.2011.653735.

Patton, Tracey Owens. “Final I Just Want to Get My Groove On: An African American Experience with Race, Racism, and the White Aesthetic in Dance.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol. 4, no. 6, Sept. 2011, pp. 104–125, citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1059.8903&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Prichard, Robin. “From Color-Blind to Color-Conscious.” Journal of Dance Education, vol. 19, no. 04, 25 Mar. 2019, pp. 1–10, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15290824.2018.1532570, 10.1080/15290824.2018.1532570.

Schaefer, Brian. “Dance in the Age of Black Lives Matter.” Dance Magazine, 1 Dec. 2016.

Walker, Ayo. “Traditional White Spaces.” Journal of Dance Education, vol. 20, no. 3, 2 July 2020, pp. 157–167, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15290824.2020.1795179, 10.1080/15290824.2020.1795179.

Author Interview – Maya Simmons

Q: Why did you choose to write about your particular topic for the project?

A: I chose to write about racial bias in dance education because it is a topic I have rarely seen any information on and it is something many dancers, including myself, deal with every day. Due to the fact that I see instances of racial bias every day, I felt as though if we were to highlight those same issues within dance, it would force many people out of their comfort zone. The leaders in the dance world have been stagnant and set in their ways about what a dance class should look like and what the dancers are learning. I want to change that, because there is always room to grow and learn new things, especially in dance. If these changes start to happen in dance, it is possible that other areas in the performing arts could be influenced for the better.

Q: With this contest, we want to feature pieces that challenge and discuss Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. How do you feel your piece accomplishes that goal?

A: My piece tackles the societal concept of race and its relationship with dance. The divide that we see throughout the world caused by racial discrimination is addressed in many different topics: everyday life, the prison system, and the war on drugs, but I wanted to make sure my piece addressed racism in dance. My piece discusses how systematic racism has seeped its way into the dance world while challenging those rules that were set in terms of what dancers are learning and what teachers are teaching. My piece should get through to a lot of leaders in the dance world, especially here at Elon. Many people are ready for a change and bringing awareness to the situation will hopefully bring that change.

Q: How do you feel the genre of the project helped you effectively communicate to your audience? What were the advantages of this genre in particular?

A: Because we were able to use all rhetorical elements in the piece, I feel as though I was able to get my point across and provide some influence. I could use the information from credible authors who have also done research on this topic. I used their logic and my own in combination to get my points across in terms of what information I wanted to relay. I brought in emotional descriptions from authors that would possibly encourage the readers to see the topic from my eyes and how important it is.

Q: What did you learn through the process of research and completing this project, and/or the experience of preparing it for publication?

A: I learned that writing does not always have to be limiting and stagnant. We were given freedom in every project and paper in that class, so I felt like I was coming out of the writing slump that high school usually brings out. I also learned more about my own experiences as a dancer and a writer. I can combine my two talents and make something that can be useful in the future. The class helped me sharpen my technical skills overall as well.

Q: How has your writing process changed throughout your time at Elon? How do you feel English 1100 fostered that change?

A: English 1100 was unlike any English class I’ve had and my professor made all the difference. English is a topic that people either love, dread, or are scared of. I did not realize how much I loved it and that it was something I could pursue in the future until I got to that class with Professor Daniel Burns.

Q: What advice would you give to students who are currently enrolled in ENG 1100, might want to complete a similar project, or are interested in publishing in Phoenix Rhetorix?

A: If you are interested in doing a project like this, I recommend finding something you are really passionate about. It was clear through my classmates’ work that they all chose topics that they were passionate about and wanted to see a change happen. However, I think that goes along with the actual writing piece of it, because writing and finding research is a challenge in itself.

Writing takes practice and the right people guiding you to be able to go in depth in whatever topic you are choosing.

ENG1100 Faculty Interview – Dan Burns

Q:What is your overall approach to teaching ENG 1100?

A: My ENG 1100 courses are organized in a dialogue-driven format that thrives on curiosity and critical thinking as my students and I develop topics, approaches, and assignments that will best serve their disciplinary interests at Elon. Since those interests might be tentative or exploratory at this early point in their academic careers, I see my role as both an ally and a sounding board for their ideas. Guided by learning objectives that stress rhetorical awareness, intercultural competence, research, and argumentation, our collaborative community of practice also works to encourage a deeper understanding of each student’s writing process. Arguably, this emergent process is the true subject of the course while their highly individualized, content-related focus provides motivation for risk and reflection in their work.

Q: What do you hope students get out of completing this particular project?

A: I hope the project affords students a sustained opportunity to reframe their experiences, positionalities, and perspectives on issues of social justice and empowerment. The Phoenix Rhetorix Call for Submissions also offers a scaffolded and sequenced context for student writing that reaches a wider college writing audience beyond their course-related peer review and assessment. Sharing their ideas with that expanded community provides additional motivation and inspiration for putting forth their strongest work. On this practical level, writers can expect plenty of support and excitement for their ideas from the PR team.

Q: In completing this project, did your student face any particular challenges? If so, how did you help them navigate those challenges, and/or how did they work to overcome them?

A: The student writer’s research was focused, incisive, and motivated by a local context that gave the topic—racial bias and dance education curricula—a force and immediacy her peer readers found compelling. We discussed reinforcing this targeted context by framing bias in the history of dance, including a range of important figures from Alvin Ailey to Joan Myers Brown and Misty Copeland. Against this backdrop, Maya examined the way Eurocentric dance movements continue to be valorized as core academic requirements while more diverse curricular advances are relegated to the status of electives. Her ability to identify a blind spot in current dance education programs and rhetorically situate it within the larger framework of current university-wide diversity initiatives is an important first step for realizing more equitable learning outcomes in her field.

Q: What was the most rewarding part of working with your student on this project?

A: Being an additional reader on the project gave me the opportunity to deepen my own knowledge base of the subject. For example, my lack of lived experience with respect to her field-specific problem necessitated a different approach to revision and editing. I began to think of our process as a kind of reciprocal mentoring, in which she guided me through the experiential side of a major navigating these omissions on a practical level while I thought about how it fit into a larger DEI-themed picture. Working through the process with the student in this more balanced way taught me far more about the subject than I would have been ordinarily capable of contributing as an outside reader. In turn, this relationship inspired me to read and critique more effectively.

Q: What advice would you give to students who are currently enrolled in ENG 1100, might want to complete a similar project, or are interested in publishing in Phoenix Rhetorix?

A: One of the unlikely figures I look to for inspiration on the writing process is the modernist architect Louis Kahn, who said this about design, “When you have all the answers about a building before you start building it, your answers are not true. The building gives you answers as it grows and becomes itself.” Following this logic, the most exciting part of beginning your writing career in college is not using it as a tool to reconfirm what you already know about yourself and your relation to the world. Rather, it should be about actively seeking opportunities for risk and reinvention in a new, potentially unfamiliar context you’re invited to embrace. To paraphrase Kahn, Phoenix Rhetorix affords one such opportunity as it provides students with a purpose and a platform for “growing and becoming” their best selves by boldly seeking out a neglected or under-examined aspect of their knowledge base.