Through the people not property project, Elon law students are digitizing bills of sale of those who were enslaved in North Carolina.

They often have no name but instead a general description of physical traits. Age? Family? Place of birth? Forget it. What do they all have in common? Each carries a price tag.

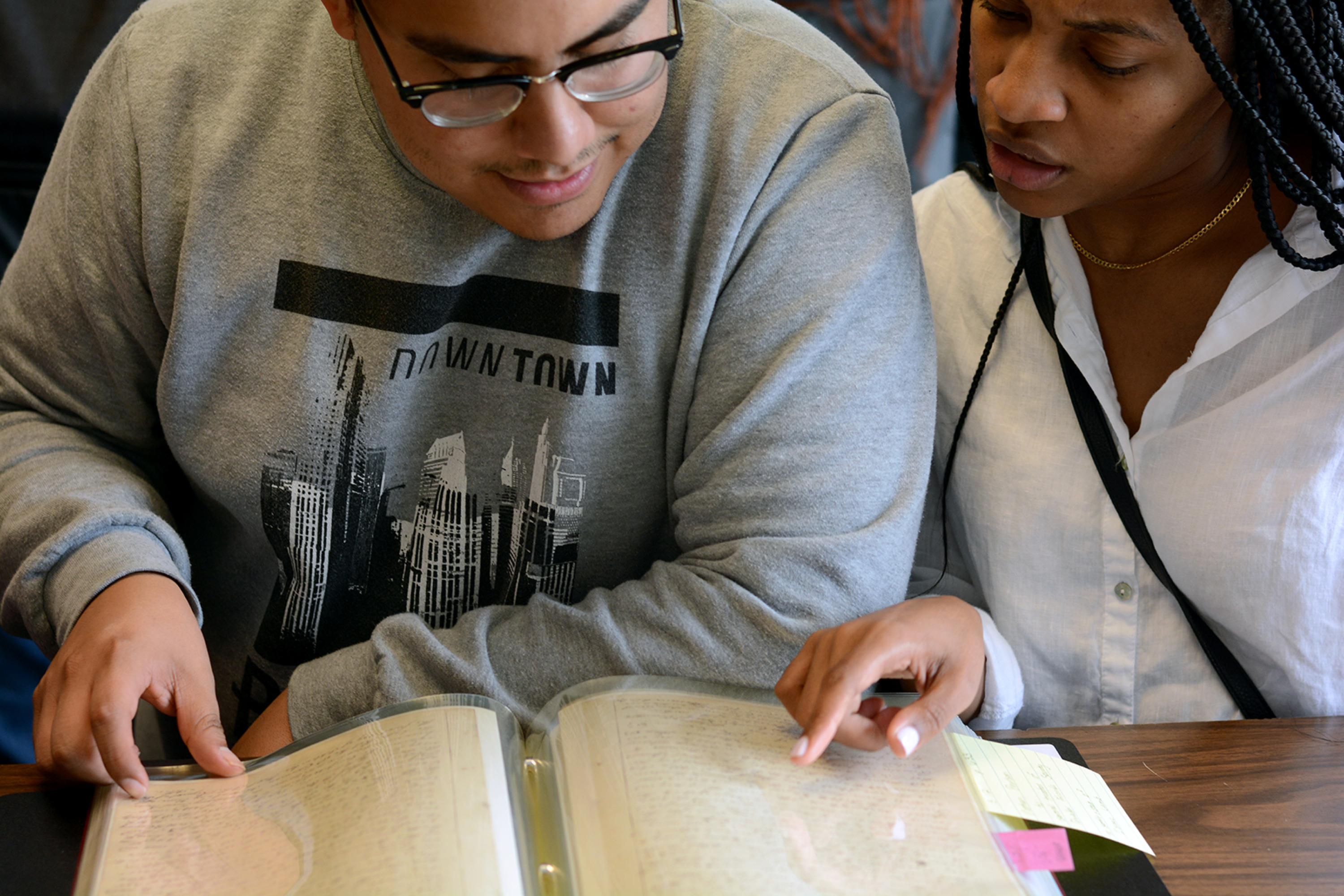

For nearly a year, Elon Law students have spent dozens of hours transcribing pre-Civil War bills of sale from the Guilford County Register of Deeds Office as part of a larger effort to build a searchable database of digitized records tied to North Carolina’s history of slavery. The People Not Property Project is a collaborative endeavor between the University of North Carolina at Greensboro University Libraries, the North Carolina Division of Archives and Records and several local registers of deeds, among others. UNCG received a grant of nearly $300,000 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission to digitize thousands of slave deeds and bills of sale with help from more than two dozen North Carolina counties participating in the program.

In Guilford County, efforts to transcribe records are being led by Register of Deeds Jeff Thigpen with assistance from Elon Law. And the process is slow. Legibility is a big obstacle. So are particular phrases and terms that take time to decipher. Then you have the sheer volume of deeds in Guilford County. Only a quarter of deeds already identified in records have been transcribed — sales that involved upward of 600 people treated not as individuals, but as commodities.

And there are still records of sale turning up inside the Register of Deeds. There’s no estimate on how long the process will take at Elon Law, let alone elsewhere in the state. “To literally see a price point on people’s lives was shocking. It’s inspired me to work for people who don’t have voices, or power or influence,” says Andrew Parks Carter, a first-year Elon Law student who grew up in Guilford County and a volunteer with the pro bono program at the law school. “To me, not hiding our history is important. These are public records. I’ve lived here most of my life and I never knew these records were here.”

Julianna Kober, the Elon Law student project manager for People Not Property, finds inspiration in her work from her family history. The Maryland native lost a dozen ancestors in the Holocaust. The only record that her relatives ever existed is a cherished family photograph that survived World War II. “There’s a generational aspect to this project,” Kober says. “This history has been in the back of my mind. How can we give others the same kind of connection I’ve been fortunate to have?”

Julianna Kober, the Elon Law student project manager for People Not Property, finds inspiration in her work from her family history. The Maryland native lost a dozen ancestors in the Holocaust. The only record that her relatives ever existed is a cherished family photograph that survived World War II. “There’s a generational aspect to this project,” Kober says. “This history has been in the back of my mind. How can we give others the same kind of connection I’ve been fortunate to have?”

Other students who volunteer for People Not Property offer similar motivations. Much of Noah Trotter’s extended family in South Carolina can only trace its lineage to the Civil War. Records of her ancestors stop there. Her mother’s last name is “German.” The first-year Elon Law student said her family assumes that at some point, when an ancestor was purchased, his name was listed as “German” in property records because his owner was of German descent. “It can be frustrating to translate things but seeing the open exchange or how they sold people, it’s a great reminder of how far we’ve come,” Trotter says.