Assistant Professor of Biology Jessica Merricks spoke about the COVID-19 vaccines at the Tuesday night meeting of Tectonic Plates: Alamance County's Science Café.

Now that COVID-19 vaccines are on the market and available, promising an end to the pandemic, the challenge is getting as many people vaccinated against the virus as quickly as possible.

Though logistics of the rollout will require patience, public perception of the vaccine and its safety could be the biggest hurdle to herd immunity.

“These vaccines are safe. … I can’t reiterate enough how important it is for everyone to get vaccinated. This is the best way to ensure you and your community are protected,” Assistant Professor of Biology Jessica Merricks said Tuesday during a meeting of Tectonic Plates: Alamance County’s Science Café.

About 40 people from Elon and the community attended her presentation, “COVID-19 vaccine: Is it safe for me to take?” during which she condensed the complicated science of our immune systems, vaccines, and how they work into easily understandable terms. At the end of the session, she responded to about 25 questions from the audience — dispelling rumors and myths, clarifying earlier points and directing them to additional sources of information.

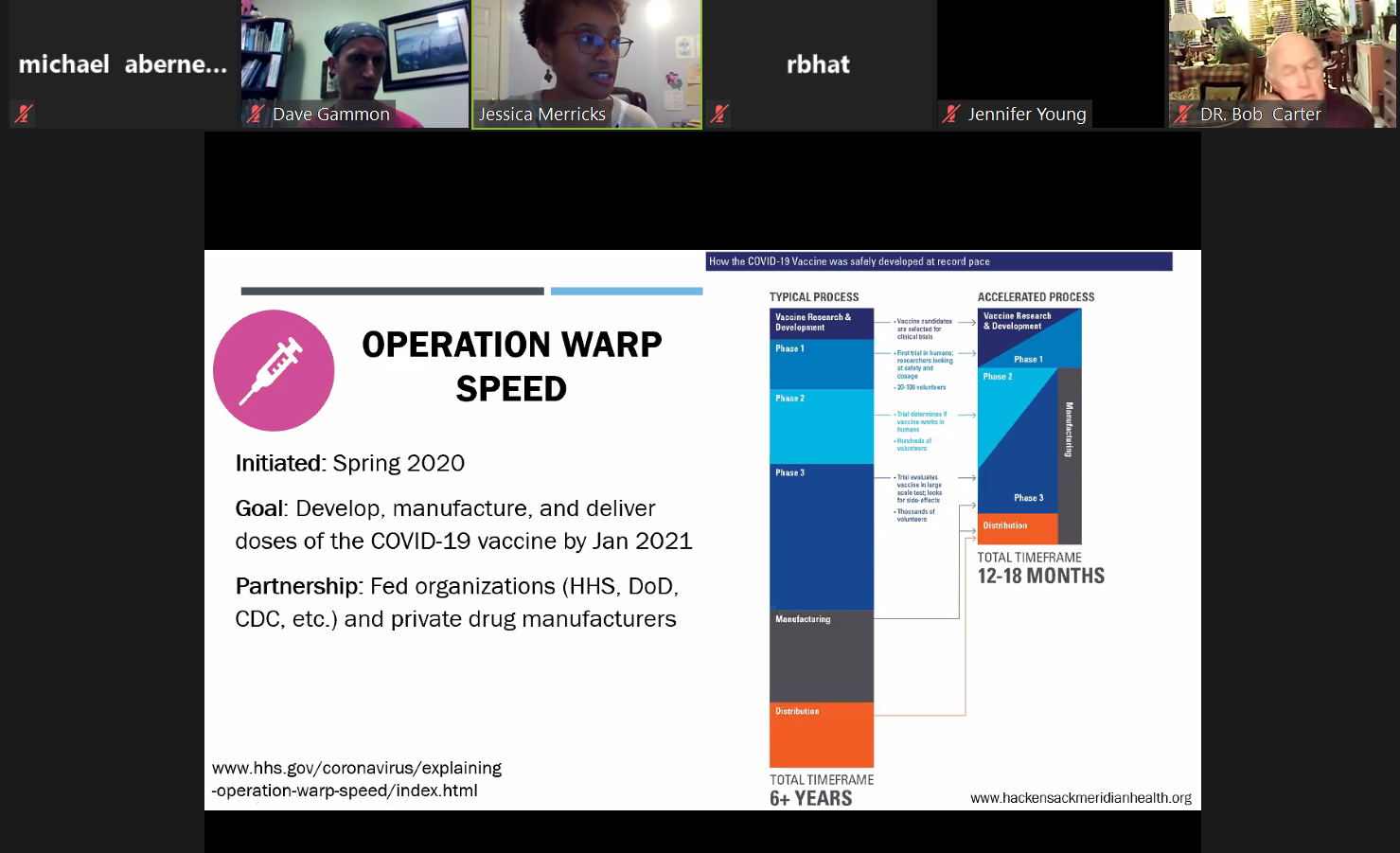

“Scientists have not cut corners when it comes to this vaccine,” Merricks said. “Though this is the fastest science has ever developed a vaccine, it was not a rushed job. This vaccine went through the same process, the same phases of clinical trials with thousands of people, and with the same rigor as other vaccines. The data have been evaluated by scientists and experts. There is no reason to feel like these vaccines can’t be trusted.”

Merricks teaches science primarily to non-science majors at Elon. Besides the foundations of biology, her objective is to get all students to think like scientists. That means learning how to evaluate sources of information for credibility and scientific accuracy.

“I am not a medical doctor, but you can trust what I say about this vaccine,” Merricks said. “I am a scientist, I have studied this science, and I have read the studies on this vaccine.” She directed attendees’ questions about specific medical risk factors or conditions to physicians.

Vaccines work by exposing us to a small, inactive amount of the virus, triggering our bodies’ immune response. Our immune systems “remember” previous infections and respond to fight them with antigens. Most vaccines in the past have used small, inactive pieces of a virus inserted in a harmless virus, “like an old cold virus,” Merricks said. The approved COVID-19 vaccines are a medical breakthrough in MRNA vaccines, using synthetic pieces of a virus’ molecular structure that give our bodies instructions on how to make antigens for the virus.

The COVID-19 vaccine was able to be developed within two years of its first appearance due to decades of research into other coronaviruses and because scientists mapped its DNA sequence early in 2020. Vaccines typically take 10 to 15 years to move from development, through clinical trials in animals and humans, to FDA approval, and finally to the public. Only about 6 percent of vaccines make it to market.

“Under normal circumstances, this slow process is a good thing, because we know a vaccine will do exactly what it’s supposed to do. We just can’t afford to wait this time,” she said, adding that trials showed around 95 percent efficacy in the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines with few adverse side effects. The most common vaccine side effects are inflammation around the injection site and the potential for a low fever. Very few people have serious reactions, such as anaphylactic shock.

Skepticism of the vaccines varies among demographics. Polls show Asian and Hispanic Americans are most likely to seek out vaccination. The Black population is the least likely to trust the vaccine’s safety. That distrust stems from a history of mistreatment, Merricks said, and that Black communities will need more targeted communication around the vaccine to encourage its use.

Other questions answered Tuesday night:

Q: Why do we need two injections?

A: So the body gets enough of the virus’ information to recognize and defend against COVID-19 in the future.

Q: Can you mix the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, getting one dose of each?

A: No. You should know which brand of vaccine you are getting and communicate with medical professionals during the vaccination process.

Q: Will we need to be vaccinated every year?

A: We don’t know yet. That depends on a number of factors, including how the virus may mutate over time and how long our bodies retain the antibodies to fight COVID-19. It may take a year or more before we know how often we will need to be inoculated.

Q: Can children get the vaccine?

A: Not yet. The vaccines have been approved for ages 16 and up. That’s why everyone who can get the vaccine needs to get the vaccine to prevent the spread of COVID-19 to those who can’t be vaccinated.

Q: Is it safe for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding to take the vaccine?

A: Though researchers didn’t explicitly study the vaccine in pregnant women, there is no biological reason a pregnant woman shouldn’t get vaccinated. A vaccine can’t affect the genetic information or development of a fetus.

Q: Are vaccines harmful, and do they cause other conditions?

A: No. Vaccines contain elements like mercury, but in smaller amounts than we ingest in regular food and even breast milk. The inactive pathogens in vaccines also cannot make you sick.

“There’s no need to be afraid of what’s inside the vaccine. It’s safe and can’t make you sick.”

Q: Is there the potential for 5G technology to trigger something in the vaccine that will become harmful in the future?

A: No. “This is physically and biologically impossible.”

Q: Will an MRNA vaccine change your DNA?

A: No, this is impossible. It can’t interfere with your genetic code.

Q: How do we know the long-term side effects?

A: The short answer is that we don’t. The long answer is that we have a general idea and we know enough about vaccines to understand how they work. So far, trials and signs point to no negative side effects.

Q: Why do we have to continue wearing masks even though we may have already been vaccinated?

A: We don’t know how long after vaccination we might still be able to transmit the virus. We have to continue to mask and social distance until a majority of the population is vaccinated.

—

Tectonic Plates is organized by Professor of Biology Dave Gammon and hosts presentations every second Tuesday from September through May. Meetings are open to the public. More information is on the group’s Facebook page.

Upcoming presentations include:

- Feb. 9: Jordan Claytor, University of Washington, What happened after the dinosaurs all died?

- Mar. 9: Andrew Hawkey, Duke University, Epigenetics and brain development: What Dad smokes could affect his sperm and children

- April 13: Bryan Luukinen, Duke University, Gardening and environmental pollutants

- May 11: Jeff Causey, Causey Aviation Service Inc., What’s next in aviation: drones and urban air mobility