Before her December graduation, Mara Weisman L’21 published an article in the official journal of the American Immigration Lawyers Association to explain a law that puts nearly 50,000 people at risk of deportation despite their childhood adoptions by families in the United States.

It happened more often than you might think.

With the best of intentions, families in the United States adopted children from overseas decades ago, only to overlook paperwork or – in some instances – mistakenly assume an adoption agency filed naturalization documents with the federal government.

And today, due to a loophole carved into law, as many as 50,000 international adoptees now living as adults in the United States are at risk for deportation, a discovery often made following an arrest or an application for federal benefits.

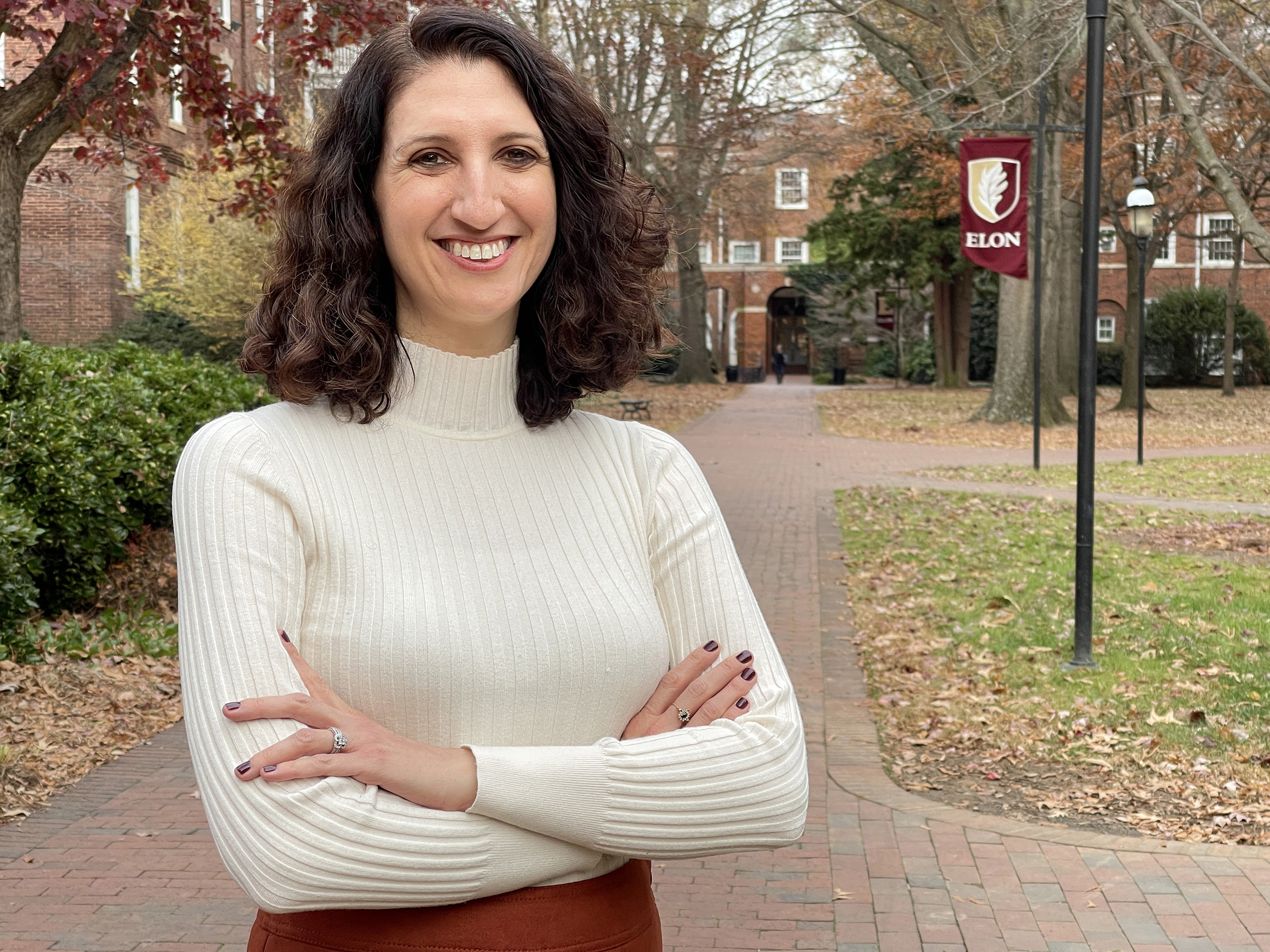

“The shock of ‘Oh my gosh, I thought I was a U.S. citizen and I’m not,’ is traumatic,” said Mara Weisman L’21, who wrote about the issue in a prominent immigration law journal shortly before her December graduation from Elon Law. “And some of them never find out and just continue to assume they’re citizens.”

“The Plight of International Adoptees: Exclusion in Law Causes Thousands of International Adoptees to Face Deportation” was published by the American Immigration Lawyers Association in a fall issue of AILA Law Journal.

The roots of the issue date to the passage of the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. Weisman writes in the article how Congress was attempting to find a solution for internationally adopted children who had not completed the naturalization process. There was a catch: the law would only apply to adoptees who were in the United States and had not yet turned 18 at the time the law took effect on February 27, 2001.

As Weisman describes it, the omission “resulted from a political compromise to appease conservative lawmakers who did not want to extend citizenship to adults who had previously committed crimes.” If noncitizen aliens are unaware of their naturalization status, adoptees facing criminal charges might accept a plea bargain – especially for nonviolent crimes – before realizing they will be removed from the country at the completion of their sentences.

Citizenship status also affects the ability to apply for government medical assistance, secure employment, obtain student loans, and even receive legal identification that can make it impossible to travel by plane, train, or bus.

What to do? Weisman suggests three actions:

- Give judges the authority to make recommendations against deportation, a power that had been removed in 1990 when Congress rescinded a procedure known as “Judicial Recommendation Against Deportation” established decades earlier. Criminal defendants would still serve sentences but not necessarily be removed from the country.

- Nonprofit organizations can host educational opportunities for criminal defense attorneys about the nuances of immigration law so that any time they represent clients who are international adoptees, they can offer informed guidance on whether to make guilty pleas.

- Congress should close the loophole and grant citizenship to those excluded from the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. Weisman proposes a solution with additional changes to the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2021, which has stalled in Congress. She advocates for even stricter language for those who have committed unresolved crimes while allowing for citizenship for adoptees whose visas have already expired.

“A revision of the law is necessary to correct a problem that has had devastating effects on many international adoptees over the past decades,” she writes in the conclusion of her article. “Legislators would do well to remember the Biblical command, ‘The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.’”

Weisman’s interest in immigration law stems from her own experiences both before Elon Law and during her legal studies as an Advocacy Fellow, Academic Fellow, and teaching assistant. While in law school she also served as president of the Jewish Law Students Association, chaired the Elon Mentoring Program, and participated in the Moot Court Board.

She is currently studying for the New York Bar Exam in February and credits Associate Dean Sue Liemer and adjunct professor Jessica Yanez for inspiring her to submit the article to AILA Law Journal. Weisman also earned academic credit in Elon Law’s Humanitarian and Immigration Law Clinic and she praised Assistant Professor Katherine Reynolds for the learning experience.

“My work on this article helped solidify my desire to pursue a career in immigration law and I hope to work with immigrants through securing their status, reuniting them with family members, and helping to prevent deportation,” Weisman said. “Eventually, though, I would like to transition to policy work, where I can hopefully help influence new legislation that will amend injustices in the law.”