Spiewak shared about his journey as a child in Europe during World War II with the Elon community.

“I was a happy child with no worries in the world,” Nathan Spiewak told the crowd gathered in McKinnon Hall on Wednesday, March 30.

Spiewak grew up in Paris during the late 1930s and early 1940s, and during the event at Elon he talked about walking a mile and a half to school, playing with his friends and the mischievous things he would get into.

But at nine years old, that normal childhood was turned upside down. He was separated from his parents during World War II and spent three years on the run from the Nazis while his parents were sent to different concentration camps.

Spiewak, now 88 years old and the grandparent of Elon student Adina Speak ‘24, recounted his harrowing account of surviving the Holocaust. He doesn’t remember being afraid at the time, but now as he thinks back, he is well aware of the severity of the situation, as more of its survivors are passing away and some people wrongly doubt that the Holocaust even happened.

“Every year, there are fewer and fewer survivors to tell this story,” Spiewak said. Therefore, he’s been so adamant to share his experience, even being one of the 52,000 interviewees that director Steven Spielberg spoke with for his film “Schindler’s List.”

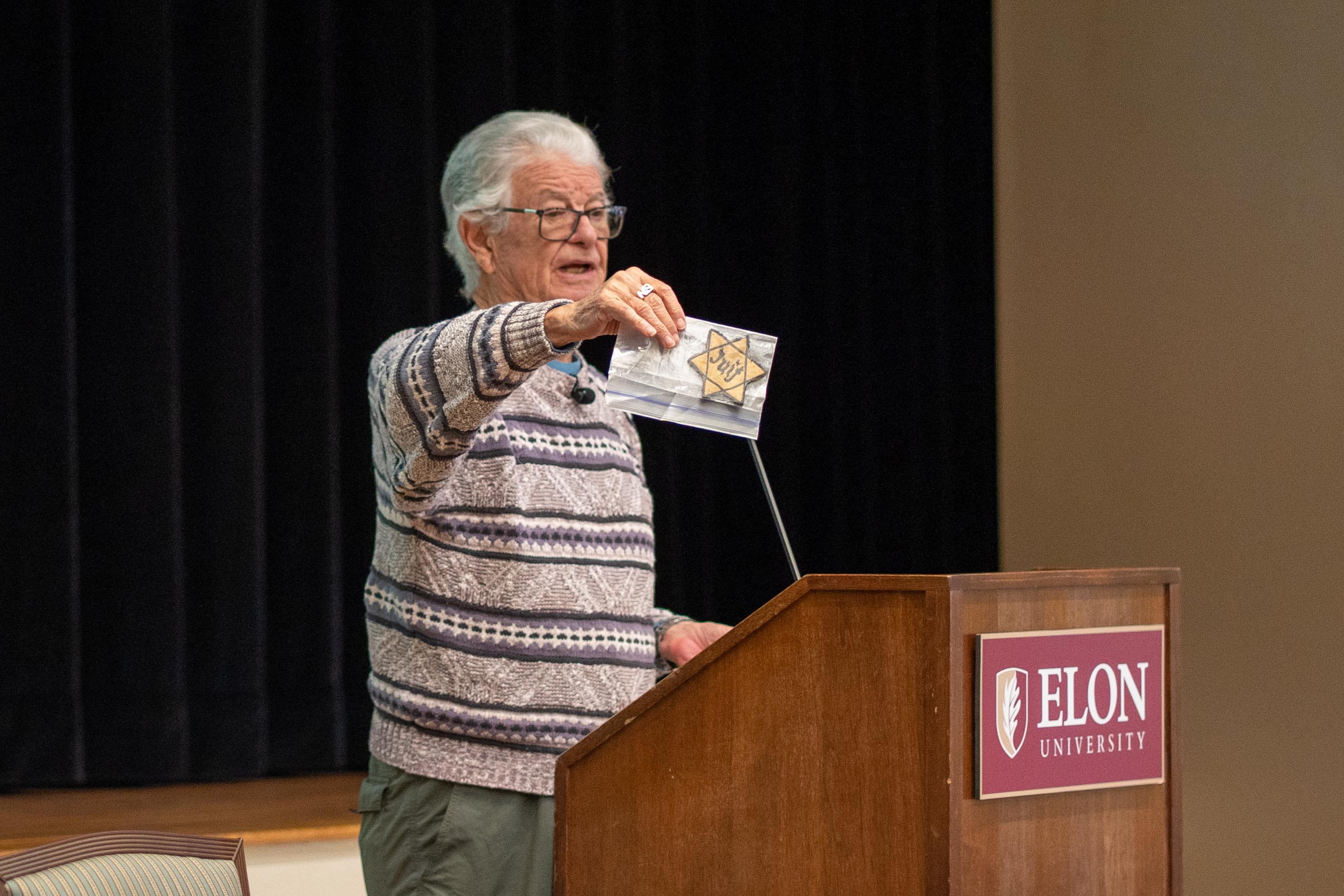

The Nazis invaded France in 1940, but Spiewak didn’t immediately realize things had changed. It wasn’t until nearly two years later that all Jewish people were required to wear a yellow Star of David on their clothing.

It was then that Jews were forbidden to eat at restaurants and to enjoy entertainment events and outdoor spaces. There was also curfew imposed from 8 p.m. to 7 a.m.

“One evening, I arrived home after playing in the street with my friend 10 minutes past curfew. I got the first spanking my father ever gave me. At that time, I didn’t understand why it was such a big deal,” Spiewak said.

Even at school, he was ostracized for wearing the yellow star. Kids he initially thought were his friends no longer played with him. “I used to go home crying to my parents. I told them I don’t want to wear the yellow star. My father explained that I should be proud of that and that I was special,” he said.

The running for Spiewak started on July 16, 1942, when he and his mother were arrested by the French police in the Velodrome d’Hiver (Vel d’Hiv) roundup. His father was working two shifts and slept at his place of work. Packed like sardines on a bus with other women and children, Spiewak and his mother were sent to the Vel d’Hiv.

At 10 years old, Spiewak remembers having a nice team eating and playing with other Jewish kids while being held at the Vel d’Hiv. Although, he and his mother were luckier than most having to only spend five days there due to his father going to the president of the company he worked for and getting them released.

However, a month later, the police returned to his home and told them to pack one suitcase each before being transported. Spiewak remembers the officer telling them they’d sent “to be with our kind.”

However, a month later, the police returned to his home and told them to pack one suitcase each before being transported. Spiewak remembers the officer telling them they’d sent “to be with our kind.”

On their way to the police station, his father intentionally dropped a suitcase to distract the officers and his mother told him to run.

“I wasn’t a fast runner, but I’m lucky I escaped,” Spiewak said. After escaping, he walked for miles before eventually making it to the apartment of a family friend. When they were released from the Velodrome, this was a plan put in place just as a precaution.

Spiewak spent a week with the family friend hiding in a small closet under the stairs when they were able to get in contact with his cousins living in Italian-occupied Nice. At the end of 1942, his cousins came to take him back to Nice, removing his yellow star and giving him a new name.

For a while, Spiewak lived with his cousins and spent some time in Italy after the Americans invaded Sicily. They eventually returned to France after a close call with German tanks that were arresting Jewish people.

He ended up living with a non-Jewish family for the remainder of the war. His uncle returned to take him back to Paris. Remembering the night that he saw his father again, Spiewak was overcome with emotion seeing a man that looked like what he remembered.

“One evening, I asked my father, ‘Why wasn’t there a mutiny against the Nazis since there was such a large group?’ He told me that each one believed that they will survive,” Spiewak said.

Following his discussion, Spiewak took questions from the audience. One student stood and spoke, not to ask a question but to tell Spiewak how much of an inspiration he is to all Jewish people.

“If you have been moved tonight to light a flame of hope where there is despair, if you have been inspired to bring peace into your life, to repair a broken relationship, … motivated to live more proud of your faith and heritage and beautiful practices – then tonight was by all accounts a resounding success,” said Mendy Minkowitz, Elon Chabad Community affiliate.