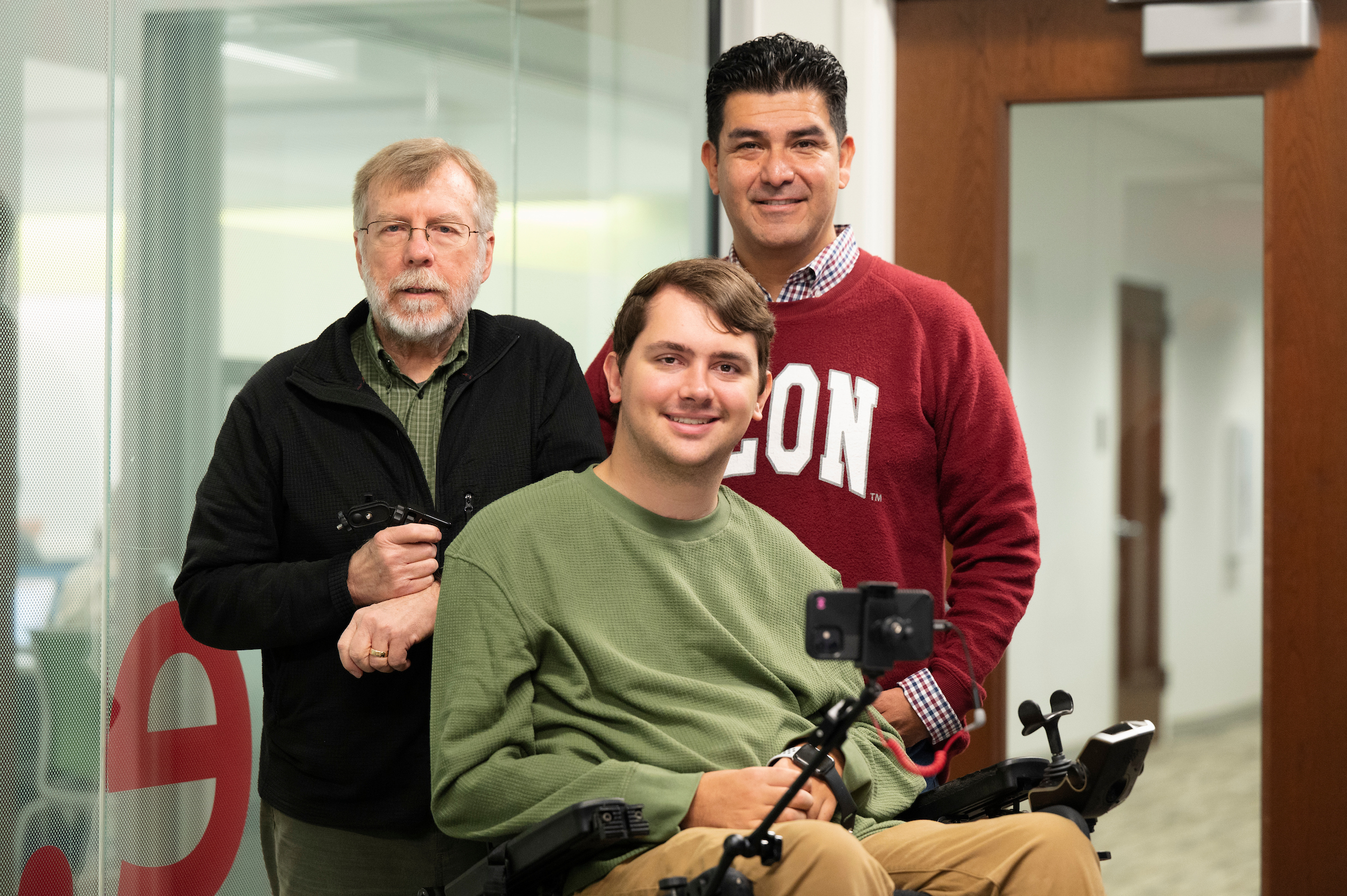

Andrew Hartle ’23 knew that operating a camera would be a challenge, but with help from communications faculty Israel Balderas and Randy Piland, he found an inventive solution.

As Andrew Hartle ’23 sat in the back of the classroom on the first day of his Multimedia News Production course in the spring of his junior year, his anxiety quickly escalated. The course involved creating two substantial video packages that would require him to shoot and edit video, set up lighting and sound, take photos, write and serve as on-air talent.

It’s a daunting task for any journalism student as they develop their skills, but especially for Hartle, who is paralyzed from the chest down, including his fingers with only limited mobility in his arms. By the second class, Hartle approached Assistant Professor of Journalism Israel Balderas with his concerns.

“I said very bluntly that I’m a little terrified of this class right now,” Hartle says. “I’m nervous and anxious about this and I’m not sure how this is going to work. I’m sure that wasn’t incredibly easy on him either.”

Balderas had previous experience with students with disabilities who needed accommodations, but not on this scale and not in a skills-based course. How could he ensure that Hartle could successfully complete a course with such a heavy emphasis on camera work, while also maintaining academic and industry standards both for Hartle and for the other students?

Together, they set out to develop an innovative solution.

A Unique Challenge

A Burlington native, Hartle was a competitive swimmer in high school and hoped to pursue swimming in college as well. But on Sept. 26, 2018, during a senior class trip to San Juan, Puerto Rico, Hartle dove into the water and hit a rock, shattering his C6 vertebrae. He spent a week in a hospital on the island before being transferred to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and ultimately the Shepherd Center in Atlanta. Despite the challenging recovery, he still graduated from high school on time.

“It went from ‘I need to swim 14 hours a week’ to ‘I now am in survival mode. I’m just trying to make sure I don’t die in this hospital in San Juan,’” Hartle says. “A few months after that, it became less survival and more what can I get back? What can I do to adapt to this lifestyle?”

Hartle chose to attend Elon so he could remain close to home in the aftermath of his accident, and he quickly set his sights on the journalism program. His first major hurdle academically was figuring out how to write papers when he can’t type on a computer. He mastered writing using an iPad and stylus by the time he began his journalism courses. But when he enrolled in Multimedia News Production — a prerequisite for many upper-level journalism courses — he had no experience operating a camera at all, much less with a disability. After their initial conversation at the beginning of the course, Balderas consulted his department chair and Elon’s disabilities resources office.

“This isn’t a ‘you get extra time on a quiz’ accommodation,” Balderas says. “This is how do we make a reasonable accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act to figure out what do we do with a camera? How are we going to do lighting? How are we going to shoot standups in front of the camera?”

The director of disabilities resources at the time interviewed Hartle about what he wanted and contacted other schools about accommodations for quadriplegic students in experiential courses. In the meantime, Balderas, who is also a lawyer, dove into the literature on disability law. He found research on hearing and vision disabilities, but very little on how to help people with extensive mobility issues with skills-based work that typically requires physical ability.

“My experience with disabilities resources has been fantastic during my time at Elon. Anything I’ve asked for, they’ve been 100% with me,” Hartle says. “This was unique because how many times does a quadriplegic come into your office saying, ‘How do I work a camera?’ to a bunch of people who didn’t go to school to learn how to work a camera?”

With little information available and no significant feedback from other schools, Hartle and Balderas began brainstorming on their own. Balderas scoured YouTube for tutorials on camera equipment for wheelchairs, but most of what he found was for people who still had mobility in their arms. During his time as a broadcast journalist, he once worked with a video editor who was quadriplegic, so he knew an answer had to be out there.

“If I knew anything about Andrew at that point I knew two things,” Balderas says. “He was dedicated, because he was in my class, and I knew that whatever I came up with, he would try. That would be at least 50% of our challenge.”

An Innovative Solution

After finding one specialty rig with a hefty price tag, Balderas approached Senior Lecturer in Communication Design Randy Piland about helping him develop a more efficient and cost-effective idea. Though Hartle struggled to push the buttons on a camera, he was comfortable with a touchscreen. Balderas is secretary-treasurer of the Society of Professional Journalists, and in his experience, growing numbers of reporters are using smartphones to capture professional-quality video as technology advances.

Piland built a monopod that clipped to the footrest of Hartle’s wheelchair with a mount at the top to hold Hartle’s iPhone at eye level. They synced the phone to an Apple Watch so he could record 4K video, zoom and adjust other settings using only his thumb. He could pan the camera by moving his power wheelchair while the monopod held the phone steady. Though it felt like an insurmountable challenge at the beginning of the semester, with his adapted equipment, Hartle now thought he could not only complete the course but excel in it.

“It went from ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do with this’ to ‘this is actually fun to do,’” Hartle says. “It was a little overwhelming at times, but by the end of it, I felt like I could have done anything asked throughout the class.”

Balderas also adjusted the class structure to meet the needs of both Hartle and his fellow students. He shifted the projects to be team-based instead of individual so Hartle would always have someone with him in the field and to reflect changing industry safety guidelines. The SPJ now discourages solo reporting after a West Virginia multimedia journalist was struck by a car during a live shot in January 2022. Balderas was also honest and vulnerable with the entire class about the reasons for the changes.

It made me remember this isn’t necessarily a huge disability. It’s just the way I live life, but that doesn’t mean I have to lower my standards.

“I remember having a meeting in front of the class and saying, ‘I’m asking you to trust me. I’m asking you to help me because I can’t do this without you,’” Balderas says. “If we truly believe in diversity, equity and inclusion, this is it. We need to confront students who need our help and say, ‘We got you.’ Is it going to require more? Absolutely. It just so happened that we succeeded; he succeeded. But it’s OK to be vulnerable and uncomfortable.”

Hartle excelled in the course and has continued to use his rig for assignments in upper-level courses. He and Balderas are now conducting research together in hopes that other students and educators can learn from their experience. They gave a research-in-progress presentation and submitted a co-authored paper to the Broadcast Education Association this fall in which they outlined the current research about college students with physical disabilities, detailed the teaching and learning process and outcomes from their own case study, and recommended areas for further exploration.

Hartle also took Balderas’ Media Law and Ethics course, which cemented his goal to attend law school after graduation. He says his experience in the Multimedia News Production class gave him the confidence to pursue his dreams on his terms.

“It made me remember this isn’t necessarily a huge disability. It’s just the way I live life, but that doesn’t mean I have to lower my standards,” Hartle says. “It means I might have to work a little harder and things might be done differently, but at the same time I should never lower my quality of work compared to those who are able-bodied.”