How Elon’s Central Power Station played a significant role in the institution’s growth during the 20th century.

There was a time when a quaint and squat building was the lifeline of Elon University. Standing two stories tall and outfitted with every convenience needed for a turn-of-the-century lifestyle — a tub, shower, lavatory, washing machine, iron and ironing board, electric hot plate and a seemingly unlimited energy supply — Elon’s Central Power Station was one of the most important buildings on campus.

“Really, at that time it was the Hilton of the campus,” wrote W.B. Terrell, Class of 1925, in a first-person account of his time working there as a student.

In 1900, the Southern Convention, which oversaw the operations of then-Elon College, voted to approve the Twentieth Century Fund capital campaign to complete the Administration Building, the main building on campus that housed male students, and other enhancements. Changes to East Dormitory, which housed female students, were completed years prior. By 1902, however, enrollment had increased “beyond capacity,” with administrators calling for a new dormitory, according to the March 1912 issue of the Bulletin of Elon College. Two years later, the board of trustees issued a $20,000 bond “for the purpose of erecting and equipping a new Dormitory or making other improvements.” However, President William Wesley Staley was adamant that no buildings should be erected without heat, light and water, which meant “a larger outlay of money than we have yet thought wise to risk,” the Bulletin reported.

Staley resigned in June 1905 (he had been presiding from his home in Virginia), while remaining on the building committee, and Emmett Leonidas Moffitt was elected Elon’s third president. The board renewed its authorization to issue $20,000 in bonds, but like his predecessor, Moffitt felt that “it would be economy on our part and will greatly promote the interest of the institution in every way, to put in a central heating and lighting plant to supply heat and light for all three buildings,” the Bulletin reported him saying. The board finally accepted these recommendations and voted to borrow an additional $15,000 to build the new dormitory as well as central power, water and heating plants. By the summer of 1906, construction was underway in “time for fires in the fall.”

According to documents in the university’s archives, a select group of Elon students worked at the power plant and each earned a “self-conferred PHD” upon graduation with their academic degrees. The PHD in question stood for “Power House Devils.” Ross M. Rothgeb, a 1918 alumnus, served as the superintendent of the power plants and approved and agreed the students earned those self-conferred “PHDs.”

“The old Power House has long since been torn away and replaced by the modern plant across the highway,” Terrell wrote. “Memories still linger with those who earned their PHD as Power House Devils.”

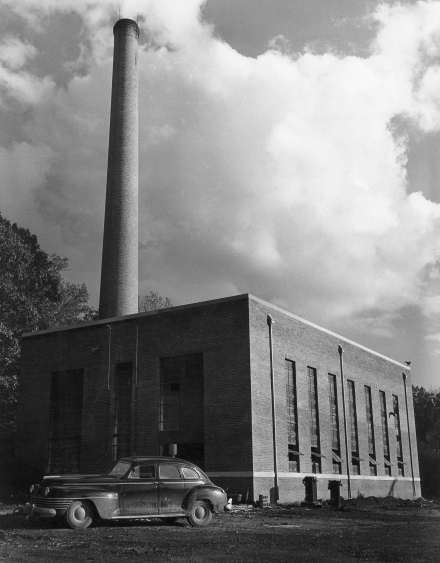

Indeed, the original power plant eventually became insufficient for the growing institution, which by the 1940s needed major renovations and new buildings. Informed of the “precarious conditions” of the existing heating system, the trustees voted to borrow the necessary funds. “Elon’s 43-year-old powerhouse gave up the ghost and a modern new plant nears completion on the north side of East Haggard Avenue,” a July 29, 1948, article from the Christian Sun reported.

The new power plant began operations in November 1948 and supported the newly constructed Alumni Gymnasium, Virginia and Carolina residence halls, McEwen Dining Hall and 50 years of Elon’s growth. As technology advanced, the second iteration of the power plant became obsolete, with the campus’ heating system being decentralized in 1998.

Twenty-five years have passed since the power plant was demolished. While we don’t know exactly where it stood (somewhere on Young Commons near where the Carol Grotnes Belk Library is today), the various academic and support buildings it once powered still stand — a reminder of the engine that once powered Elon.