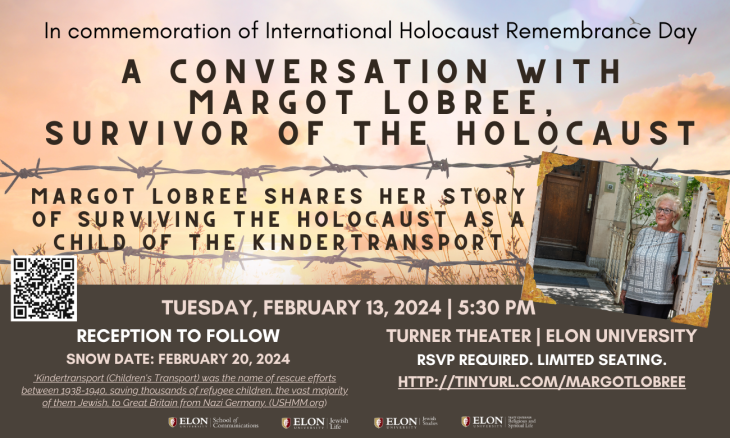

More than 350 students, faculty, staff, and community members gathered in person or tuned in online to hear Holocaust survivor Margot Lobree's message of hope during her visit to Elon on Tuesday, Feb. 13.

“Now, I want you all to take a moment and imagine as a child, coming home one day, and being told that all alone, you’re going to leave your entire family, your friends, all your belongings, and go to a foreign country, with a foreign language, and live with complete strangers. That is what happened to me at the age of 13,” Holocaust survivor Margot Lobree explained to those gathered on Tuesday, Feb. 13, in Turner Theater to hear her story.

Lobree, 98, recounted the challenges she faced as she was displaced from her home in Germany and separated from her family to those gathered in Turner Theater in the School of Communications to hear her story. Director of Jewish Life Betsy Polk and the Jewish Life Team collaborated with Associate Professor of Journalism Rich Landesberg and the School of Communications to bring Lobree, who now lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, to Elon.

Lobree spoke to a full house of more than 200 students, community members, faculty and staff, including University Chaplain Kirstin Boswell along with members of Elon’s senior leadership. Over 150 additional viewers watched a livestream of the event, which remains available for viewing.

Lobree recounted her journey out of Germany through Kindertransport, which was an organized effort to rescue children in Nazi-controlled territories and transport them to safer locations. Lobree, like many children in the program, was separated from her parents, her friends and even her older brother, who was transported to the Middle East.

Lobree was taken in by a sponsor family in London, where she said members of the family constantly reminded her of her refugee status in their household. She was expected to cook, clean and just be grateful for the fact she was still alive.

Once full-scale war broke out in Europe, her sponsor family evacuated London for safety, leaving her and the maid to fend for themselves in the house. She moved to a house hostel 45 miles outside of London and spent the next two years with other refugee girls. Eventually, she met, Julie, who would become a lifelong friend and who would help her find a new home in London.

After originally relocating to live with Julie’s aunt and uncle, the pair found their own apartment and then decided to make the great move to the United States in April 1944. Lobree was still a teenager at this point, and it took many years to pass before she understood the impact of what happened to her throughout this whole experience.

After originally relocating to live with Julie’s aunt and uncle, the pair found their own apartment and then decided to make the great move to the United States in April 1944. Lobree was still a teenager at this point, and it took many years to pass before she understood the impact of what happened to her throughout this whole experience.

“I lost the loving attention of a family. I was deprived of a good education and growing up under normal circumstances. I was deprived of learning how to be an adult in a safe environment,” Lobree explained. “And I only understood the trauma and the tragedy of my entire experience as an adult.”

Eventually, Lobree was invited to visit Frankfurt, Germany, in 1996. She realized the difference with the new generation and decided to view the situation from a different perspective. “Holding onto anger is a waste of energy. That is not productive. It is destructive. Anger, and anything really, when it’s over, just let it go. I’m glad I did.”

Her message again and again was to “be aware, be vigilant, be proud of who you are, be positive, be hopeful.”

She explained that the greatest difference in moving to America was the feeling of freedom to walk the streets without a gas mask or go out without a government-mandated curfew. To her, it was almost overwhelming. “I’ve always loved strawberries. Throughout the years of the war, I didn’t see a single strawberry. When I came to New York with all these vegetable stands everywhere, all I ate for a whole two weeks was strawberries! That in itself just shows the invaluable freedom.”

Lobree has previously shared her story with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which is available to watch online.

—

Christy Brook contributed to this article.