How a small tool used by OB-GYNs can hold the key for the future of clinical care

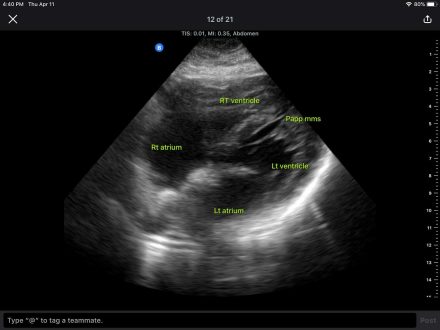

Picture it: a tool the size of a TV remote that can be used to examine and answer a question about the human body. It sounds futuristic, but Associate Professor of Physician Assistant Studies Cindy Bennett is working with students in the PA program at Elon to illustrate how this technology is a reality through Point of Care Ultrasounds (POCUS).

Bennett is a teacher with a medical background. After working as an OB-GYN, she left private practice to follow her love of teaching at the middle, high school and eventually college levels. Landing at Elon, she began teaching anatomy, physiology and reproductive medicine. She also began learning about a new skill using ultrasounds. Although her experience with ultrasounds was limited to examining pregnancies and reproductive organs, she began learning how POCUS provided a new use. POCUS, Bennett explains, is a quick ultrasound completed during someone’s physical exam.

In the past, ultrasound machines were huge and expensive, spanning about five feet, weighing 20 pounds and costing roughly $300,000. Now ultrasound machines can be created in smaller units that can connect to a mobile phone, only costing $2,500. Health care providers can carry the device in their pocket and conduct quick ultrasounds looking for a particular piece of information. “The idea with POCUS is you have a clinical question, you go get that one answer, and then you stop scanning,” Bennett says.

Additionally, the advantages of POCUS have increased global and socio-economic accessibility. The affordability and size of the device allow health care providers to improve care in niches of the world that might not have that care otherwise. For instance, she says, a provider with this device can hook it to their iPhone in the middle of Ecuador at a tiny clinic. They can then call an expert in Raleigh, North Carolina, or Washington, D.C., and learn how to treat a patient with the resources at hand.

For Bennett, this is a skill her students need to learn. Some years ago, she developed a program that focused on POCUS, ensuring that students would gain a level of proficiency in the skill, and illustrating the need of purchasing the smaller devices as teaching tools for the PA department.

Starting in 2017 with one device, Bennett recruited volunteers to undergo ultrasounds so she could train herself in the best teaching techniques. She also spoke with different equipment representatives, inquiring if they would supply the university with ultrasound machines for teaching purposes. That trial year confirmed she could teach anatomy using POCUS. She developed a unit about the anatomy of the head and neck as you see it by ultrasound. She then made sure students had seen that anatomy in the anatomy lab through donor dissection before bringing them to the ultrasound lab and showing them those same things on living people.

While teaching the skill of POCUS, Bennett simultaneously taught students the basics of using any type of ultrasound machine. “This is the way the future’s going to go,” she says. “I want them to be on the front edge of this and ready to use this skill when they get out.”

The program expanded in the years following Bennett’s trial run, adding three additional units. The format included four POCUS sessions and workshops, dividing students into small groups. Guest physicians and physician assistants who were using POCUS in their clinics were also brought in to work with Bennett as preceptors. However, COVID-19 changed the program’s format, causing Bennett to alter how students learned POCUS. The hybrid learning during COVID confirmed for Bennett that POCUS education could also be achieved during the second (clinical) year of PA education as a part remote, part hands-on curriculum.

“This is the way the future’s going to go. I want them to be on the front edge of this and ready to use this skill when they get out.”

“What I wanted was to give [second-year students] POCUS and teach them not just how you can use an ultrasound to see anatomy, but also what clinicians were doing. That’s tough when people are remote,” Bennett explains. “So, I put together remote learning, something that was part remote and part coming in for testing.”

Last year, 16 second-year students completed the program under the hybrid model, enhancing their ability to get jobs and improving their vantage point for starting jobs. This year, the number grew to 29. “It’s great to see students’ education doing more for them because they’re learning this skill,” Bennett says.

The program has continued into its second year using the hybrid model. Though Bennett says she is still working out the kinks of the Elon POCUS program, it is well on its way to becoming a national model for using POCUS in the classroom. She presented her work at the Physician Assistant Education Association conference in New Orleans in October.