Fall 2025: Caroline Bienfang

More Than the Music:

An Analysis of Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Halftime Show as Symbolic Protest and Political Resistance

Caroline Bienfang

Journalism, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show was more than a musical spectacle—it became a visually charged act of protest delivered on one of the world’s largest entertainment stages. His performance reframed the broadcast arena as a site of political resistance, challenging viewers to confront issues of race, identity, and power. Textual and content analyses highlight how Lamar used visual symbols, lyrical language, and performance strategies to address issues of systemic racism, cultural marginalization, and national identity. The use of messages, references to historical betrayal, and the visual of a split American flag were among the images used in the show, which helped transform a platform for global entertainment into a platform for social commentary. The research examines how Lamar incorporated coded messages into a highly commercial platform by cross-referencing audience discourse, media reception, and academic frameworks such as African American folklore and “Poetics of Inversion.” Lamar aligned his performance with the broader tradition of Black protest art, drawing inspiration from figures such as Gil Scott-Heron and Langston Hughes. The findings of this research assert that the concert transformed expectations for typical broadcast performances by fusing spectacle and resistance, thereby reinforcing hip-hop’s position in political discourse.

Keywords: textual analysis, race, television, hip-hop, Super Bowl

Email: cbienfang@elon.edu

I. Introduction

The NFL’s Super Bowl halftime has at times been used as a global platform for social commentary, with some performances displaying it more explicitly than others. In particular, Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime performance in 2025 highlighted many important, culturally significant subjects. The performance occurred in February when the United States nationally recognized Black History Month. As a Black performer known for his political and social commentary, the messaging in his music had much significance at this time, particularly in light of the divisive presidential election that had been completed a few months earlier.

Kendrick Lamar is an award-winning hip-hop and rap artist recognized as one of the greatest performers ever and the first non-classical or jazz musician to win a Pulitzer Prize for music. His album “DAMN” in 2017 was critically acclaimed for its ability to bring mainstream recognition to hip-hop artistic depth. Lamar has been known throughout his career for using his creative flair to highlight social and political issues within the United States. In his album “Overly Dedicated,” he used anecdotes to explore the mindsets of individuals involved in gang warfare lifestyles. His album “To Pimp a Butterfly” was released during the Black Lives Matter movement; the song was an act of resistance to assimilation into white culture.

This research will use textual analysis to uncover the meaning behind the symbolism displayed in Lamar’s performance at the 2025 Super Bowl halftime show through visual symbols, lyrical messaging, and performance techniques. This study will examine how Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime performance used a global platform to communicate political resistance, specifically addressing systemic racism in the United States.

II. Literature Review

Music has long served as a powerful gateway into conversations about social and political issues. Collective empowerment has been a powerful tool for unifying people of various backgrounds using social criticism and opposition in these spaces. Symbolic protest has often involved creative expression, particularly in musical concerts. These symbolic protests have been crucial in bringing about change and amplifying the voices of underrepresented groups. For decades, scholars have examined how artists in various specialties have employed visual symbolism, lyrical messaging, and performance techniques to resist cultural, political, and social injustices. Kendrick Lamar’s performative resistance is a display of explicit political statements. It evokes an emotional response from viewers that fosters collective engagement and understanding to inspire change. Central to this study is the role of rap music in social movements, where both lyrics and performance serve as a form of protest and a means of cultural storytelling. From the civil rights movement to contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter, hip-hop and rap artists have used their platforms and artistic abilities to criticize injustices and advocate for social change.

Symbolic Protest and Performative Activism Portrayal in Media

Prior research has examined the relationship between symbolic protest and performative resistance; such research has highlighted how marginalized groups have used performance art to challenge dominant narratives. Performative art in music and other forms of artistic expression has historically had the unique ability to combine embodiment, duration, and relationality to create a more unionized audience and develop strong social statements that challenge social norms (Ventzislavov, 2023). This framework is critical to understand and compare when analyzing Lamar’s halftime show as an example of powerful visual and performative rhetoric.

The National Football League has seen examples of symbolic protest before, including Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the National Anthem to protest police brutality and racial injustice. One study concerning Kaepernick demonstrated how symbolic acts of protest are often reframed by media to delegitimize the intended political messaging by instead focusing on symbols of patriotism, such as the American flag or the U.S. military (Graber, Figueroa, & Vasudevan 2019). In addition, Black performers who infuse cultural expression into mainstream events with global platforms, such as the Super Bowl halftime show, often face criticism, which, in turn, reinforces the systemic pressures that many marginalized voices encounter today and have encountered for centuries (Gammage, 2017).

Rap Music as a Medium for Social Protest

Historically, rap music has long functioned as a strong foundation for social and political resistance, particularly in addressing systemic racism, police brutality, and other forms of inequality (Lusane, 1993). Rap music combines lived experience and artistry, often challenging social norms and serving as an expressive outlet for artists to share their lived experiences (Martinez, 1997). Among the studies to build upon this theme are a content analysis of rap songs that were released in response to George Floyd’s murder (Mozie, 2022) and how rap helped pinpoint root causes of issues – such as institutional racism – underlying the 1992 Los Angeles riots (Martinez, 1997). Individuals in government positions often fail to address issues within marginalized communities, which therefore threatens and exacerbates the crisis even more (Lusane, 1993).

Systemic Racism and Cultural Marginalization

Many of Kendrick Lamar’s songs, lyrics, and performative symbols convey commentary on systemic racism and cultural marginalization. It is crucial to understand systemic racism, as it is a necessary foundation for understanding the more profound meaning behind the symbolism he used in his halftime performance. Cognitive biases and segregation directly contribute to racial inequality (Banaji & Fiske, 2021). Multiple symbolic gestures within a performance directly correlate to our understanding of systemic racism in America. Backlash against Black performers also demonstrates how systemic racism manifests itself in public perception of cultural expression (Gammage, 2017). Constraints are often put on marginalized communities, economic or political barriers, or due to a fear of being labeled “deviant” or internalized dominant discourses (Martinez, 1993). Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality identifies the overlap that exists between both racial and gendered identities and how they create distinct forms of oppression. The framework used in Crenshaw’s theory is useful in analyzing Lamar’s performance, particularly moments that appear within the intersection of race, gender and class (Crenshaw, 1995).

Kendrick Lamar’s Political Rhetoric

Previous research reveals how Lamar’s music and performances largely reflect strong critiques of violence and racial oppression, highlighting his artistic ability to unify individuals by incorporating “poetics of inversion” to challenge social norms and injustice (Lowman, 2022). In this manner, he challenges dominant American stories and brings up problems like systemic racism through careful use of symbols, self-narrative, and religious allegory. Other scholars have note rap music’s ability to convey a fear of a “broken system” by using lyrics that critique large, institutionalized subjects such as healthcare, housing, and education (Martinez, 1993).

Prior research has underscored how prominent Black artists have used high-profile performances as platforms to reach global audiences for acts of symbolic protest and political resistance. Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show builds upon this notion, resonant with themes of racial identity, cultural expression, and systemic racism and injustice. While scholars have previously analyzed Beyoncé’s halftime show as an act of resistance (Gammage, 2017), Lamar’s performance introduces perhaps an even more extensive demonstration of symbolism through lyrics and visual storytelling to make social and political commentary. This research seeks to highlight the expanding role of Black artists in challenging the dominant narrative on one of the largest global platforms.

Research Questions

RQ1: How does Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime performance employ visual symbolism, lyrical messaging, and performance techniques to communicate themes of political resistance and social commentary?

RQ2: What recurring themes of systemic racism, cultural marginalization, and social resistance emerge through Lamar’s use of symbolic imagery and lyrical content?

RQ3: How does Lamar’s halftime performance draw upon established traditions of rap music as a form of cultural resistance and political protest?

RQ4: How does Lamar’s halftime show use symbolic elements to challenge dominant cultural narratives about race, identity, and American patriotism?

This research is significant as it extends pervious research about rap music as a way for marginalized communities to share lived experiences. This research also gives a unique opportunity to explore and analyze how significant events and televised performances can combine entertainment with political commentary. Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show performance occurred during Black History Month. It was performed in front of a global audience, including the current 47th president of the United States. The timing of his performance makes this research even more substantial.

This study is also essential as it allows one to understand other examples of symbolic protest in mainstream media. This research is increasingly vital in a digital age with constantly changing media and opportunities for commentary because public discourse can distort such messaging. Additionally, this research will contribute to broader discussions on race, representation, and performative activism in popular culture.

III. Methods

Through a textual analysis approach, this study examines Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime performance as an example of political opposition and symbolic protest. With a focus on visual symbols, lyrical content, and other performance components including stage design, costumes, and choreography, the study explores a range of Lamar’s performance elements. Textual analysis is a form of qualitative research in which researchers closely examine cultural objects, including songs, writing, and visual symbols, to ascertain their meaning, applicability, and social implications (Lorenz & Assmann, 2021). Examining social media platforms, nationally known news sources, comment sections, and academic sources helped uncover deeper relevance and social consequences of the performance.

The textual analysis specifically examines visual symbolism, lyrics, and a variety of performance techniques. Some of these performance techniques included stage setup, wardrobe design, and the formation of the background dancers. This analysis explored themes such as racial identity, cultural expression, and political resistance. Media commentary and the background offered by previous peer-reviewed research were also consulted to identify social messaging behind Kendrick Lamar’s performance symbolism.

To respond to RQ2, the study closely analyzed the song choices for this performance, as well as the lyrics within those chosen songs. By consulting previous research, interviews, and other media commentary along with online news articles, the study uncovers recurring themes, political messaging, and cultural messaging within the music.

RQ3 and RQ4 were explored using media and public reactions to the performance. Sources for this analysis included online articles, blogs, tabloids, and other opinion pieces, such as social media comments, to understand the perceptions of media outlets, as well as individual audiences. Included will be a comparison of reactions to Beyoncé’s 2016 Super Bowl halftime show, which received backlash from media outlets and audiences for her presumed political and social stance. In addition, a content analysis will be conducted on a selection of media articles about Lamar’s Super Bowl performance.

In addition, the study compares Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl performance to Beyoncé’s 2016 halftime performance, identifying shared themes and differences in tone, message, and reception of their performances. This comparative analysis reveals how cultural expression and protest dynamics have evolved within the context of globally reaching high-profile performances.

IV. Results

Visual Symbolism: The Performance as a Political Game

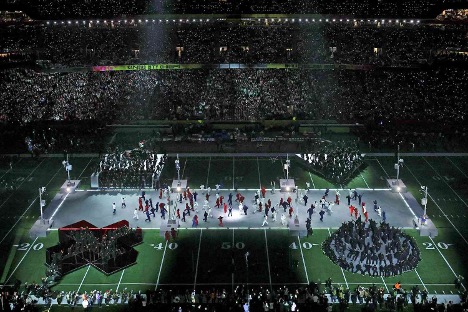

One key attribute that is extremely necessary to highlight when assessing RQ1 is the stage design of Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show. More specifically, it is essential to highlight how the stage design is believed to match a PlayStation controller, with symbols like X, O, triangle, and square (Figure 1). The stage design created an intricate narrative about institutional imprisonment and survival within the United States. Lights inside the audience spelled out the messages “START HERE” and “GAME OVER,” thus transforming the stage into a symbolic playing field, symbolizing the gamification of life and the illusion of free choice in a society defined by oppression (Jahmal, 2025). This theory is tied in with the idea that rap music is a strategic survival method that has long been used to navigate social constraints (Martinez, 1997). Similarly, symbolic performance is believed to be a tool widely used to resist dominant narratives (Lowman, 2022). In performances (particularly film), Black visual expression can simultaneously be dangerous and potent, mainly when expressed under surveillance and control systems (Rahman, 2024). This fear of surveillance and control drives these perceptions about stage orientation and its underlying message of being controlled. These perspectives further frame Lamar’s performance as a cultural critique, where game imagery and the illusion of playfulness are used for protest and political commentary.

Figure 1 (Watts, 2025)

Figure 1 (Watts, 2025)

Storytelling through Visuals

The light that illuminated the crowd was believed to have been made by drones used to spell out the phrases mentioned, “START HERE,” “GAME OVER,” and “WRONG WAY.” This imagery was spelled out when Lamar knelt before the Buick GNX on stage. These phrases complemented the stage’s video game controls and mimicked the instructions. More than that, the setup was a symbol of real-world structural barriers and systemic misdirection, particularly for Black Americans (Dolak, 2025). The PlayStation-style stage featuring the controller icons (X, O, triangle, square) was a visual reinforcement of the idea that life is a rigged game under the constraints made by institutions (Dolak, 2025). The show’s art director, Shelly Rodgers, explained that the setup was designed to reach younger audiences and symbolize Lamar’s journey to achieving the American Dream (Dolak, 2025). Supporting sources offered insight into Black visuality, particularly within performance art and film (Rahman, 2024). Black visuality often involves symbolism and evasive strategies for navigating surveillance systems and those considered radically controlled (Rahman, 2024). Throughout his performance, the choreography symbolized a battleground, with dancers falling to the ground in a familiar position, often seen in crime scenes outlining victims’ body positioning (Dolak, 2024). The artist created a gamified environment that scrutinizes and expresses Black identity, addressing significant systemic issues like police brutality and systemic racism (Rahman, 2024). The artist invites the audience to witness the performance and question the oppressive systems it critiques through its use of imagery (Rahman, 2024).

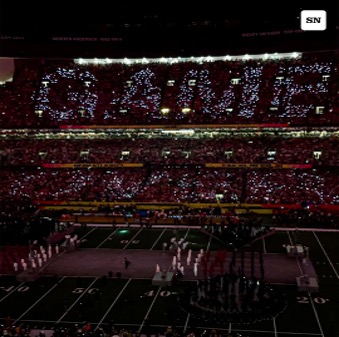

The second half of the performance seems to embody a prison yard. Continuing with the game metaphor, this stage orientation and visual symbols highlight systemic traps and rigged pathways. These visual cues are used to signal the consequences that occur when resisting oppressive systems. It represents how the choices for marginalized communities are often illusionary (Simonson, 2023). This metaphorical prison symbolizes the central state and how it operates in reality (Dolak, 2024). The stage orientation reflects upon the growing academic argument that society must shift from the term “criminal justice system” to more accurately represent its proper function, a system of control rather than justice (Simonson, 2023). This imagery contrasts national colors, making it a visual rejection of American exceptionalism, therefore framing the United States as a place of entrapment for the oppressed (Figure 2). Lamar’s performance further underscores the ongoing captivity experienced by many Black Americans despite the notion that it is a country that promises freedoms through national ideals (Simonson, 2023).

Figure 2. (Sporting News, 2025)

Protest Through Song Choice

Strategic song choices selected by Kendrick Lamar served as acts of lyrical protest. Lamar’s enormous success in the music industry can be equated to a poetic and meaningful lyrical message; this performance highlights his use of music as a means of protest. Songs included “Not Like Us,” “DNA,” “TV Off,” and “Man at the Garden,” all with powerful messages of systematic injustice, authenticity, and rebellion. One meaningful lyric is, “They tried to rig the game… But you can’t fake influence.” This lyric captures the main points of surviving within unfair systems of control and oppression and recovering truth through authenticity. By applying his “poetics of inversion” technique, Lamar transforms influential cultural icons into criticisms of radicalized stems of power (Lowman, 2022). While the song “Not Like Us” critiques industry exploitation and betrayal, his “DNA” signifies pride in Black identity. Rap music has been used as an alternative to hierarchies of power for decades (Martinez 1997). With each song enhancing Lamar’s message of autonomy and critique, the setlist created a cohesive message reflecting a politically divided America (Dolak, 2025). These songs had the power to transform the Super Bowl stage into more than just a musical venue by grouping each of them into one setlist; more so, such songs became a platform for symbolic resistance based on lyrical and cultural memory (Martinez, 1997).

Themes of Systemic Racism, Cultural Marginalization, and Social Resistance

Samuel L. Jackson emerged as Uncle Sam within moments of Kendrick Lamar’s performance starting (Figure 3). Including this element in the performance was a symbolically dense decision rather than just theatrical. Jackson pauses the performance on multiple occasions, saying, “too loud, too reckless, too ghetto” (Pace-McCarrick & Jibril, 2025). Jackson’s remarks towards Lamar serve as a reflection of Black oppression and how it is at times controlled, especially when it appears to be bold or challenging societal expectations. By subverting the Uncle Sam character and using “poetics of inversion” (Lowmann, 2022), Lamar questioned the very country it stands for. Jackson’s character also is a play on the trope of “Uncle Tom,” which historically rewarded Black obedience and punished opposition (Cambridge et al., 2008). Presenting the Uncle Tom archetype alongside the Uncle Sam figure allows viewers to examine who can talk, what is regarded as a suitable expression, and how visibility interacts with control in America.

Figure 3. (Watts, 2025)

Commentary on Reparations & Historical Betrayal

Before starting his song “Not Like Us,” Lamar pauses the performance to say, “Forty acres and a mule, the order is bigger than the music,” referencing Field Order No. 15. The 1865 U.S. military directive promised land to formerly enslaved Black people. The quick revocation of the promise has become a symbol of the U.S. government’s betrayal of Black freedom and equality. Reconstruction had begun with hope, but it soon collapsed into backlash when sharecropping, disenfranchisement, lynching, and convict leasing became widespread (Graff, 2015). Lamar’s reference pertains to greater ongoing inequity than simply to historical memory. According to Lusane (1993), there is a persistent pattern of material theft in the ongoing struggle for justice and reparations. Large institutions, according to Banaji and Fiske (2021), continue to marginalize Black people, frequently under the appearance of development, while reflecting continuous periods of betrayal. Lamar tied history and presented it together by employing symbolic protest, thereby Creating a moment of collective consciousness is a strategic choice to bring attention to “forty acres and a mule” (Banaji & Fiske, 2021).

Kendrick Lamar as Trickster / Signifyin(g) Figure

Black artists have historically placed symbolism, coded language, and passive critique to confront systems of oppression (Bailey, 2021). Deeply ingrained in African American folklore, Black Americans have long been considered “the folk,” objects of research, and symbols of “authentic Blackness” used to support power structures based on race (Bailey, 2021). In response, historical Black intellectuals, including Anna Julie Cooper and Charles Chesnutt, created “positioning” strategies (Bailey, 2021). These subdued forms of resistance are concealed in presumably conformist or acceptable societal expressions (Bailey, 2021).

Lamar seems to have followed this custom since his performance reflects folktale or what is known as “trickster narrative,” continually straying between spectacle and critique (Clark, 2025). Using Gil Scott-Heron’s line, Lamar changed the original “The revolution will not be televised” to “The revolution ’bout to be televised,” followed by “Turn the TV off” (Heron, 1971). This decision was a conscious move to reflect upon the rhetorical and symbolic layering that folklore scholars identify as a defining element of Black expressive culture. In contrast, survival often requires saying one thing while meaning another (Bailey, 2021). Lamar uses national platforms and commercial performance spaces to signify rather than assimilate. Lamar calls upon recognizing these issues by shifting dominant narratives, speaking in what some deem “code,” and exposing systemic contradictions while engaging with them (Bailey, 2021).

Cultural Visibility vs. Vulnerability

A powerful example of the tension that exists between admiration and critique of Black expression is shown when Serena Williams was spotlighted in Kendrick Lamar’s performance doing the Crip Walk during the song “Not Like Us” (Figure 4). For some audience members, this movement represented unfiltered joy and cultural pride as Serena reclaimed a dance move that had previously sparked racist backlash during her 2012 Olympic gold medal win (Clark, 2025). For others, the same action was perceived as controversial, highlighting how Black cultural expression is often recorded as deviant or criminal, depending on the audience’s perspective. Tiana Clark describes this as a “double bind” faced by Black performers, which refers to when joy is viewed with suspicion or restraint; she begs the question, “Why must our resilient joy be caged?” (Clark, 2025). Clark frames the Crip Walk moment as a long-overdue act of reclamation and resistance through performance. Not only is this example a reflection of racially coded bias, but it is also gender centered. Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality highlights how Williams’ dance is an embodiment of both racial and gender identities that are often policed more harshly when performed by Black women in particular (Crenshaw, 1995). By incorporating the dance on stage during the show, Lamar amplified this intersection of race and gender, situating Black female bodies as central to cultural resistance.

Figure 4. (Watts, 2025)

Rap as Resistance: Lamar’s Connection to Traditions of Political Protest

Lamar’s references to Langston Hughes’s poem “Harlem” reflect many historical and present injustices within the United States. In the poem, Hughes warned that a deferred dream might “sag like a heavy load” or “explode” (Clark, 2025). Lamar’s performance embodied both a release of historical pain and a critique of broken promises to members of society. In a written review of the performance, Tiana Clark connects this theme to Lamar’s lyric, “They tried to rig the game,” inferring that this performance was more than rap, music, and any performance at all. Instead, it is a commentary on systemic betrayal (Clark, 2025). As a symbol refusing to soften historical truth for mainstream comfort, Lamar employs visual symbolism in the formation of dancers in a seemingly split American flag, Samuel L. Jackson’s dual role as Uncle Sam/Uncle Tom, and the historical significance merged entertainment with critique. Just as Hughes’s poem did, Lamar’s performance did not offer closure; rather, it challenged issues at hand today and issues from the nation’s history to witness, to reflect, and maybe even to act (Clark, 2025).

Comparative Analysis with Beyoncé (2016)

Media outlets such as The Root, BuzzFeed, Dazed, and The New York Times praised Lamar’s symbolism, political critique, and layered messaging. Calling it “13 minutes of protest art,” Tiana Clark from The New York Times praised the performance’s use of “camouflaged ciphers” to provide profound critique inside mainstream format (Clark, 2025). Media sources highlighted Lamar’s capacity to balance spectacle and depth.

Beyoncé’s 2016 halftime performance offers a uniquely relevant comparison. Not only did her performance occur during the same high-profile platform that Lamar’s did, but the controversy also it sparked was strikingly similar. Both performances centered Black protest aesthetics, both using thoughtfully encoded messaging of racial and political opposition. The performances had many parallels, of which were those that challenged mainstream expectations, provoking both applause and backlash. By highlighting these similarities, it brings to stage the methods in which Black artists strategically deploy culturally relevant performances to contest dominant narratives in society. This comparison is essential to assess the broader cultural and media studies discussions.

Lamar faced backlash similar to Beyoncé’s after her Super Bowl halftime performance. Conservative commentators took to news outlets and social media, calling the performance “un-American.” The Economic Times reported that Matt Walsh, a conservative pundit, called the performance “easily the worst halftime show” he had ever witnessed. This critique mirrors the 2016 reaction to Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance and shows how Black protest still gets labeled as menacing. The complicated symbolism of the performance was understood by some viewers, while others misinterpreted or even rejected it (Clark, 2025). The backlash Beyoncé received for her performance showcases what Crenshaw identifies as the compounded oppression that Black women face: gendered and racial stereotypes exist among the way audiences interpret their artistic expression (Crenshaw, 1995). The reaction exposes the cultural unease with unreserved Black resistance, particularly in highly visible, monetized venues.

During the song “TV Off,” whether planned by Lamar or not, a performer displayed a protest flag that called for a ceasefire in the Israel-Gaza conflict. This portion of the performance was not shown by media platforms on TV streaming the event; the act was significant for many viewers. This international reference expanded the scope of Lamar’s critique far beyond the United States and unfolded into a global justice movement with this one element (Clark, 2025). The final lyric, “Turn off the TV,” was a call to action that urged viewers to consider their passive consumption closely and challenge them to interact more actively with what they see in their social environments (Clark, 2025). Based on Clark’s assessment of the performance, Lamar’s use of direct and coded protest is reinforced, highlighting this layered approach aimed to challenge comfort and demand thought (Clark, 2025).

Challenging Dominant Narratives: Symbolism, Race, Identity, and Patriotism

The dancers’ alignment in creating an American flag with Lamar in the middle was another striking and visually stunning moment from the show. Black culture and people are vital to national identity, but Black people are often excluded from its promises; the dancers’ red, white, blue, and back-to-back form reflects this split nation. This underlined Black artists’ contradiction in negotiating marginalization, criticism, and representation. Reflecting Black Americans’ complex relationship with patriotism, Lamar’s position in the center of the flag design signified both inclusion and detachment (Dolak, 2025). A review from The Hollywood Reporter underlined this event as showing “America’s stubborn division… on the largest stage possible” (Dolak, 2025). This method of turning known symbols to expose methodical errors relates to the phrase “poetics of inversion” discussed previously in this study (Lowman, 2022). Usually using performance to obtain space and voice inside institutions that often reject artists, rap music offers strategic resistance to artists using their (Martinez, 1997). By asking viewers to consider who the flag truly represents, the performance challenged American nationalism directly, elevating it beyond simple performance art.

V. Discussion

According to Clark (2025), Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show at the Super Bowl in 2025 served both as a performance and as a type of protest art through the use of profound and meticulous symbolism. Through the medium of national television, his show addressed a wide range of societal concerns, some of which were racism, incarceration, and the depiction of black people. Songs like “Not Like Us” and “DNA,” which doubled as diss tracks and criticisms of American systems, featured these symbols and elements prominently (Clark, 2025). These songs were remarkable for their representation of these themes. Additional visual symbols, such as the living American flag, a caricature of Uncle Sam, and the instruction to “Turn off the TV,” served to underline the show’s twin message of resistance and reclamation (Clark, 2025).

Lyrically, he interacted with Black literary traditions, making references to works such as “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” by Gil Scott-Heron and “Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes. He then transformed these criticisms into a kind of resistance that was focused on performance. In accordance with Gates’s theory of signifying (Moody-Turner, 2013), Lamar’s inversions are examples of cultural remixes because they reposition pre-existing language and symbolism in order to reveal inconsistencies. The performance portrays Lamar as a contemporary trickster figure who is both fun and subversive, employing coded language and sarcasm in order to undermine and challenge national mythologies. His use of coded legibility indicates that the concert was intended for Black audiences while simultaneously refusing comprehensive interpretation by the general public, particularly white audiences. This tension is framed by academics as cultural legibility against coded legibility. It is similarly demonstrated by the fact that Serena Williams’ Crip Walk during the song “Not Like Us” caused some spectators to feel delight while others were filled with controversy. This demonstrates how Black celebration is frequently referred to as a threat, since Williams was criticized for similar action in previous celebrations for sports (Clark, 2005).

The New York Times, Dazed, and BuzzFeed were among the publications that lauded the creativity and symbolism of the event. On the other hand, conservative critics, referred to the show as divisive. The criticism that Beyoncé received immediately following her performance at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2016 mirrored this backlash. This pattern of responses reveals how Black protest art is frequently stigmatized based on factors such as gender, tone, or directness during the protest.

The barrier between entertainment and political discourse is blurred because of this performance, which transforms the Super Bowl into a venue for revolutionary messaging. In addition to demonstrating that hip-hop can be explosive, encoded, and transformative all at the same time, it establishes a precedent for future protest art on commercial platforms.

VI. Conclusion

Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 halftime show is now recognized as one of the most powerful performances on one of the largest global platforms in recent memory. The performance wasn’t just musical, art, or visual entertainment; it was a multi-layered work of modern art that employed visual symbolism, sharp lyrical content, and a multitude of cultural references, calling out systemic injustices and reclaiming a global stage to uplift the voices of those that are impacted by oppression (Clark, 2025). Through this, Lamar reaffirmed rap’s role as political commentary, especially through coded messages, signifying strategies, and trickster tropes (Mood-Turner, 2013).

The show reformed what might be considered “entertainment” into a deeply layered critique of Black cultural expression. The backlash that Lamar received highlighted the fragility of Black visibility (Jahmal, 2025). His performance connected with younger, digital-native audiences by using key cultural references such as the “Squid Game” references to critique capitalism. The raising of a Palestine flag to protest the conflict during “TV Off” showed solidarity with global resistance movements (Clark, 2025). The show’s overall algorithm-era aesthetics, which combine popular culture with anti-imperial messaging, designed the protest for a digital world.

Future research could explore how different audiences interpreted or misunderstood Lamar’s symbolism as his career continued. Other research could also analyze performances like this and how they can reshape expectations for what protest art can look like in other forms of media. Ultimately, Kendrick Lamar didn’t just perform at the Super Bowl; he transformed the 2025 Super Bowl into a platform for political resistance. This research affirms that rap, spectacle, and protest are not separate forces but rather deeply connected. Kendrick Lamar’s performance proves that they can coexist powerfully on the world’s biggest stage and drive important conversations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Dan Haygood, whose guidance has been invaluable throughout my research. I am extremely grateful for the opportunity to have learned from such an inspiring and passionate teacher, whose lessons I will carry with me long after my time at Elon. I am also deeply thankful to all of my professors, mentors, and the administration at Elon, thank you for your support and guidance over the past four years.

References

Abdur-Rahman, A. (2025). To render a black world. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 37-51. https://elon.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/render-black-world/docview/3127388403/se-2

Bailey, E. L. (2021). (Re)making the folk: Black representation and the folk in early American folklore studies. Journal of American Folklore, 134(534), 385-417, 537. https://elon.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/re-making-folk-black-representation-early/docview/2630320982/se-2

Banaji, M. R., Fiske, S. T., & Massey, D. S. (2021a). Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

Chow, A. R. (2025, February 10). Kendrick Lamar rewrote the rules of the halftime show. Time. https://time.com/7214228/kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-halftime-show-analysis/

Clark, T. (2025, February 14). Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show was radically political, if you knew where to look. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/14/opinion/kendrick-lamar-halftime-art.html

Coleman, R. (2025, February 10). Samuel L. Jackson surprises as emcee of Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl 2025 halftime show. EW.com. https://ew.com/samuel-l-jackson-surprises-as-kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-halftime-emcee-8788712

Condee, W. F. (2010). Uncle Tom’s cluster: Talking race. Theatre Topics, 20(1), 33-42. https://elon.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/uncle-toms-cluster-talking-race/docview/218637914/se-2

Crenshaw, K. (2018). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. In K. Bartlett & R. Kennedy (Eds.), Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender (pp. 57–80). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429500480-5

Dolak, K. (2025, February 10). Decrypting the symbolism in Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/music-news/kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-halftime-show-symbolism-1236132476/

Gammage, M. (2017). Pop culture without culture: Examining the public backlash to Beyoncé’s Super Bowl 50 performance. Journal of Black Studies, 48(8), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934717729504

Sporting News. X (formerly Twitter). (2025, February 9). https://x.com/sportingnews/status/1888765232169820488

Graber, S. M., Figueroa, E. J., & Vasudevan, K. (2019). Oh, say, can you kneel: A critical discourse analysis of newspaper coverage of Colin Kaepernick’s racial protest. Howard Journal of Communications, 31(5), 464–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2019.1670295

Graff, G. (2016). Post civil war African American history: Brief periods of triumph, and then despair. The Journal of Psychohistory, 43(4), 247-261. https://elon.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/post-civil-war-african-american-history-brief/docview/1776154919/se-2

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, Media, Language (pp. 128-38). Hutchinson.

Challener, S. (2019, September 25). Langston Hughes: “Harlem.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/150907/langston-hughes-harlem

Keum, B. T., & Choi, A. Y. (2024). Critical social media literacy buffers the impact of online racism on internalized racism among racially minoritized emerging adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 71(6), 659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000758

Levin, B. (2023). After the criminal justice system. Washington Law Review, 98(3), 899-946. https://elon.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/after-criminal-justice-system/docview/2892071663/se-2

Lorenz, A., & Assmann, K. (2025). Defining democracy through news coverage: Democracy beat coverage by local newsrooms. Newspaper Research Journal, 46(1), 167–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/30497841251317294

Lowman, N. (2022). The political efficacy of Kendrick Lamar’s performance rhetoric. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 12(2), 65–78. https://researchebscocom.elon.idm.oclc.org/c/b2qt42/viewer/pdf/mvyyqvltk5

Lusane, C. (1993a). Rap, race and power politics. The Black Scholar, 23(2), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.1993.11413093

Mamo, H. (2025, February 13). Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl halftime show is now the most-watched of all time. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/music/rb-hip-hop/kendrick-lamar-2025-super-bowl-halftime-show-most-watched-all-time-1235899552/

Martinez, T. A. (1997). Popular culture as oppositional culture: Rap as resistance. Sociological Perspectives, 40(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389525

McGee, N. A. (2025, February 11). The complete breakdown of the symbolism, references in Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime performance. The Root. https://www.theroot.com/the-complete-breakdown-of-the-symbolism-references-in-1851760266

Mozie, D. (2022). “They killin’ us for no reason”: Black lives matter, police brutality, and hip-hop music—a quantitative content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 99(3), 826–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/10776990221109803

Pace-Maccarrick, S., & Jabril, H. (2025, February 10). Unpacking the symbolism of Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Show. Dazed. https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/66062/1/symbolism-behind-kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-performance-donald-trump-drake

Ventzislavov, R. (2023a). Performative activism redeemed. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 81(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaac/kpad006

Watts, M. (2025, February 10). All of Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl 2025 halftime show Easter eggs. People.com. https://people.com/kendrick-lamar-super-bowl-2025-halftime-show-easter-eggs-8789173