Spring 2023: Molly Craig

Read All About It: A Quantitative Analysis of

The Baltimore Sun’s Reporting Practices

Molly Craig

Communication Design, Elon University

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications

Abstract

In 2022, The Baltimore Sun’s editorial board published an apology for an historical pattern of perpetuating racism through its reporting. This study focused on how the publication framed crime coverage before and after the apology was published. Using content analysis informed by framing theory, the researcher examined a sample of “biased” and “unbiased” articles from 2013-2021 and again in 2022. The findings of the study suggest that The Baltimore Sun has changed its reporting practices since the apology, with the use of positive language contributing to unbiased crime coverage. This research suggests that the Sun is on the way to achieving the goal of using its influence to break down the barriers that have repeatedly held back individuals and communities.

Keywords: journalism, crime reporting, race relations, framing theory, content analysis

Email: mcraig9@elon.edu

1. Introduction

Crime is a complex topic that scholars often investigate in hopes of discovering a clear explanation of the causes. In Baltimore, Maryland, leaders struggle to identify and address the underlying factors that lead individuals to commit crimes. The Baltimore City Police Department documented almost 24,000 crimes in the first seven months of 2022, and leaders have been pressured to reduce the numbers (Baltimore Police Department, 2022).

Many city officials argue that historical discrimination and inequity toward individuals and communities has influenced crime problems (Fenton et al., 2022). City ordinances and federal government enactments implemented decades ago resulted from biased practices and institutions that failed to support and protect vulnerable populations. The allegations of systemic bias are supported by research – for instance, one study found that disadvantaged communities where a high percentage of individuals with low socioeconomic status live have a higher rate of violent crimes (Hipp, 2010).

News media outlets also have been scrutinized for institutional bias that fueled inequity and discrimination of marginalized individuals and communities. For example, some scholars note that media outlets frame their narratives through harmful lenses that rely on stereotypes to construct news (Entman & Gross, 2008). In 2022, the editorial board of The Baltimore Sun published an article admitting to, apologizing for, historical, racial bias in the publication’s reporting. This study seeks to determine whether The Baltimore Sun has changed how it frames crime in Baltimore City since its public admission of biased reporting.

II. Literature Review

The following section focuses on three concepts. The first section explores the role institutional injustice plays in discrimination and inequity and how it impacts crime rates in Baltimore City. The second section provides an overview of framing in the press and examines the way a newspaper’s reporting practices influence the messages readers receive. The final section examines the Baltimore Sun’s Editorial Board article, which was published on February 18, 2022, and confessed to a history of biased reporting.

Discrimination and Inequity in Baltimore

In 1910, a Baltimore City zoning ordinance was the first decision ever passed in the United States to legally promote racial segregation. This legislation stated that African Americans could not reside in a block of Baltimore City where more than half the residents were white, and white people could not live in any block where more than half the homes housed African Americans (“Baltimore Tries Drastic Plan,” 1910). The mayor at the time announced, “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidence of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby White neighborhoods, and to protect the property values among the White Majority” (Rothstein, 2015, p. 205). These patterns and practices, put in place by city leaders within an institution that is intended to serve the needs of all residents, instead catered to the advantaged residents while not investing in the underprivileged (Badger, 2015).

The city continued to segregate communities by banning white people from selling their homes to non-whites and allowing neighborhood covenants to implement discriminatory restrictions for property owners. Non-whites, especially African Americans, were left to live in overcrowded communities with poor-quality rental housing where lead, mold, and asbestos polluted the air (Grove et al., 2018). These were elements of a process called “redlining,” where specific Baltimore neighborhoods were deemed a poor financial risk, “avoiding investments into areas predominantly made up of low-income or people of color” (Abello, 2017, para. 6). According to Sindal and Newman (2022), this historic practice where banking institutions refused to lend money to buy homes and insurance companies rejected clients targeted Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods for decades.

One study found that urban neighborhoods with more economic disadvantages experienced a higher rate of violent crimes (Hipp, 2010). Baltimore’s police department reported a total of 23,663 incidents from January 1, 2022, through October 12, 2022. Aggravated assault led the violent crime list, while larceny headed up the non-violent statistics (Baltimore Police Department, 2022). Forbes Magazine has called Baltimore one of the ten most dangerous cities in the United States (Bloom, 2022). Mayor Brandon Scott noted that the continued crime issues facing the city are a “historical problem” and the past has worsened today’s problems (Fenton, Costello, & Prudente, 2022, para.15). Similarly, city councilman Mark Conway argues that when you constantly “press” on a community, it will eventually “pop,” and crime and violence will result. He encourages providing “real opportunities to folks” as a way to decrease the city’s crime (Fenton, Costello, & Prudente, 2022, para. 39).

In 2015, the Washington Post recognized that Baltimore’s government “diminished the capacity” of impoverished communities in Baltimore City to recover from historic neglect. The Post revealed, “It’s an irony, a fundamental urban inequity, created over the years by active decisions and government policies that have undermined the same people…that again and again dismantled the same communities, each time making them socially, economically, and politically weaker” (Badger, 2015, para.6).

Newspapers in Baltimore historically have played a role in institutional bigotry and media bias by running home sales advertisements that were classified by race while also informing specific marginalized groups of their restrictions from buying or renting (Durr, 2011). Litovsky (2021) expressed that these practices such as these in newspapers can stem from individual journalists, organizational routines, and the larger organization. Scholars share that such messages sent by institutions give insight into the mechanisms by which disparities arise and are perpetuated (Jones, 2002). While today, outright discrimination in the press is no longer common practice, historical practices and exposure to biased information leads to negative societal outcomes (Spinde, Jeggle, Haupt, Gaissmaier, & Giese, 2022). Damaging societal outcomes can include both discrimination and inequity. Here it is evident, as Neckerman and Torche (2007) explain, that find income inequality plays a pivotal role in crime rates, especially violent crime. This is consistent with others who proclaim the areas in the city of Baltimore with the most crime are the ones that are historically ignored and discriminated against (Abello, 2017).

Framing in the Press

Scholars around the world have studied the theory of framing in the press. Paul D’Angelo defines a frame as a “written, spoken, graphical, or visual message modality that a communicator…uses to contextualize a topic, such as a person, event, episode, or issue” that can be found in domains such as newspapers (D’Angelo, 2017, p.1). Entman emphasizes that “…media’s decision biases operate within the minds of individual journalists and within the processes of journalistic institutions, embodied in rules and norms that guide their processing of information and influence the framing of media texts” (Entman, 2007, p. 166). He suggests that journalistic institutions play a role in how frames are depicted in the media, and further states that framing news that supports one side rather than providing equal treatment to all parties is content bias (Entman, 2007).

Moreover, the way a news story is framed can have a positive or negative spin, and framing can create or strengthen biased associations (Gurevich, 2022). Therefore, it is essential to critically examine the language, angle, and selection of news reports before making a judgment because not all media news publications tell the stories in the same way (Coleman & Thorson, 2002). A large body of research focuses on how frames can influence people’s attitudes and behaviors through the selection and presentation of information. Entman argues that the power of framing is through “selective description and omission,” which includes emphasizing some facts over others or altogether leaving out information (Entman, 1993, p. 54). Scholarship has established that reader perceptions can shift depending on an article’s frame (Carlyle, Slanter, & Chakroff, 2008).

Entman and Gross argue that “the media rely heavily on stereotypes in constructing their narratives, and journalists themselves filter information through their own stereotypes” (Entman & Gross, 2008, p. 111). On study found that repeated exposure to news where African Americans are stereotypically and frequently called criminals influences negative implicit attitudes toward the group (Arendt & Northup, 2015). From this research, the practice of framing is shown as powerful tool where negative lenses often lead to stereotyping and discrimination of marginalized groups in society.

Another study examined one particular crime incident that was framed in four different ways and found that the slant in which the media covers an incident can negatively or positively shape people’s views, judgments, and understanding of an event (Fridkin, Wintersieck, Courey, & Thompson, 2017). An important factor of consideration in the media’s use of negative framing when reporting crime is the adverse consequences for victims and suspects. In a study of news framing involving the murder of a young homosexual man in Wyoming, researchers found that the consistent reference to the victim’s sexuality painted a stereotypical picture and dehumanizing narrative (Ott & Aoki, 2002). Similarly, disclosing prior convictions are often used to characterize those involved in inner-city crimes. News media outlets often construct a subjective reality that causes audiences to believe that crime is a “cultural norm” of low-income individuals living in urban areas (Parham-Payne, 2014, p. 757).

The Baltimore Sun

The Baltimore Sun is an institution that employed biased frames that harmed marginalized groups through its communication of print news. The Sun is the largest newspaper in Maryland and was founded in 1837 by a segregation and slavery advocate (Baltimore Sun Editorial Board, 2022). On February 18, 2022, the newspaper’s Editorial Board published an apology for its longtime reporting routines, which sent messages that harmed people and communities in the city. Three months after its inception, “selling slaves” ads appeared in the Sun which shows the newspaper’s role in racist practices, insensitivity, and a disregard for some humans (Baltimore Sun Editorial Board, 2022, para. 9). The article declared, “Too often, The Sun did not use its influence to better define, explain, and root out systemic racism or prejudiced policies and laws” (Alatzas, 2022, para.1).

The newspaper committed to “doing better” with more relevant and less biased reporting in the February apology (Baltimore Sun Editorial Board, 2022, para.15). The Board wrote, “… we turn the spotlight on ourselves and our institution, looking at our history through a modern-day lens in an attempt to better understand our communities, the effect we had on them, and the distrust engendered by The Sun’s actions” (Baltimore Sun Editorial Board, 2022, para. 8).

III. Methods

The literature review suggests that media framing is a powerful tool with an ability to build and shift individual perceptions through the way a story is presented. While negative frames can lead to stereotyping and discrimination of marginalized groups in society, positive frames may be useful in breaking down barriers by providing more empathetic news reports relating to distressed populations. In Baltimore City, news reports about crime are prevalent because of the high occurrence rate, and The Baltimore Sun aims to ensure its readers are informed. However, it is essential to pay attention to how reporters tell the crime stories touching city residents because the Sun acknowledged the institution’s role in biased reporting practices that facilitated prejudice. The Baltimore Sun’s Editorial Board also promised to improve the biased narratives filtered through its newspaper. In response to the apology, this study seeks to examine the research question: Has the Baltimore Sun changed how it frames crime in Baltimore City since the February 2022 public admission of biased reporting?

A quantitative analysis of the Baltimore Sun’s press coverage of crime in Baltimore City was used to address the research question. A quantitative content analysis enables the researcher to look at the frames and investigate by counting the number of biased or unbiased crime articles in the city. This analysis helped to discover whether the Sun changed its biased reporting practices. Exploring the language used in the selected crime articles allowed the researcher to determine if the newspaper adhered to its promise by implementing words that promote equity and change the narrative about marginalized individuals and the communities where they reside.

The data set consisted of crime articles sampled from The Baltimore Sun, Maryland’s largest and most prominent newspaper. The articles were randomly selected beginning in 2013 and ending in August 2022. To keep the sample random, the researcher utilized a box containing twelve slips of paper representing each month of the year. Then, the researcher drew a slip of paper from the box for each year from 2013-2021. Next, the researcher selected crime-related articles from the predetermined month for each year. This established a total of nine articles for examination from several years prior to the Sun’s public apology. Then, the same box was used but contained individual slips of paper representing each day in a particular month from March through August of 2022. The randomly selected day determined what date the researcher used to select the 2022 crime-related stories. This process generated an additional six articles for examination from the timeframe after the Sun’s acknowledgment of publishing stories that endorsed discrimination. A total of fifteen Baltimore City crime articles were collected from various months and years to observe, review, evaluate, and learn about the content included in the articles.

To interpret the data, the researcher created a coding system. The first column listed the name of each Baltimore Sun article beginning with the oldest and the most recent. Next, the date the article appeared in the newspaper was listed. The subsequent two column headings were titled “Biased” and “Unbiased,” and a checkmark was placed in the appropriate column for each article. To determine whether an article was considered “Biased” or “Unbiased,” the narrative was examined. If the article was framed with a narrative emphasizing discriminatory verbiage or stereotypes about marginalized groups or communities in Baltimore City, then a check mark was placed in the “Biased” column. However, if the article was framed with a narrative that led readers toward an empathetic understanding of individuals or communities, then a checkmark was placed in the “Unbiased” column. The “Biased” and “Unbiased” columns were crucial to the quantitative analysis because the findings were counted and used to measure the number of biased versus unbiased reporting by the Baltimore Sun.

Finally, the last two columns consisted of “Negative Language” and “Positive Language” headings. While examining each article, words and phrases were recorded and placed in the appropriate column. Words intended to construct unfavorable perceptions about individuals or communities were placed in the “Negative Language” column. Words meant to generate empathy or compassion for individuals or communities involved in the story were listed in the “Positive Language” category. The content analysis of the word choices by reporters was gauged to see if the Baltimore Sun was sincere about its published apology.

IV. Findings

The first portion of the research study analyzed framing of Baltimore City crime articles in the Baltimore Sun newspaper between 2013 and 2022. The research examined the content with a total sample size of fifteen articles to determine whether the newspaper’s reporting used biased or unbiased practices in the way it framed crime stories.

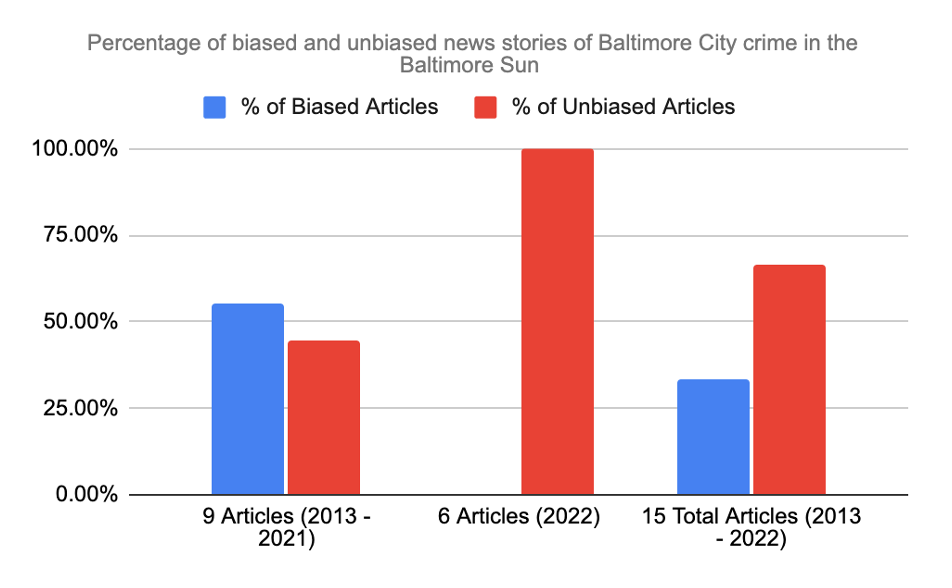

Figure 1

Figure 1

The analysis (Figure 1) found that 33.3% of the fifteen articles were deemed biased because the crime story frames applied discriminatory or stereotypical narratives about marginalized groups or communities in the report. While 66.6% of the news stories were considered unbiased, a closer examination is warranted.

Of the articles examined from 2013-2021 (9 total), approximately 56% were coded as biased. In four of the nine articles, the biased narratives were directed toward victims of crime. The lives of the victims were framed in a way to shift the readers’ perceptions. Instead of presenting the story in a neutral tone or positive slant (providing empathy), emphasis on damaging characteristics portrayed crime victims as unimportant society members. For example, in 2014, a transgender woman was killed, and the reporter highlighted her role as a prostitute. The reader was also provided with her criminal history, and the reporter painted a picture of the undesirable neighborhood where she resided.

In contrast, 44.4% of the crime articles from 2013-2021 were coded as unbiased. However, two of the four articles accentuated the neighborhoods where the crimes occurred as communities with lower crime rates. For example, a 2018 article stated that crime is “rare” in the neighborhood where a 25-year-old college graduate was killed (Anderson & Fenton, 2018, para. 21). In both articles, positive frames were used to describe the victim and the community. Furthermore, in the remaining two stories coded as unbiased, sympathetic frames were used to describe one pregnant woman and two children who were the crime victims.

Each of the six selected crime articles from March 2022 through August 2022 were presented through unbiased communication. This statistic significantly improved the overall unbiased percentage when examining all 15 articles. However, prior to 2022, the majority of Sun articles framed crime stories through a lens that fit into a biased narrative.

In addition, the research explored the language used in the same fifteen news articles and broke words and phrases into the category of either negative or positive language. In particular, a comparison was made between the language used to construct a crime news story in the years 2013-2021 to the news stories published after February 18, 2022. Four news stories (out of nine) between the years 2013 and 2021 used more positive language to present crime stories in the Baltimore Sun, while five articles used mostly or only negative language (Table 1).

Table 1

| Articles between 2013 – 2021 | Language Used | Biased or Unbiased |

| 4 | More positive language | Unbiased |

| 4 | More negative language | Biased |

| 1 | Only negative language |

In contrast, articles in 2022 relied primarily on positive language to tell crime news stories (Table 2). One article in 2022 used primarily negative language to build the crime story, yet all the articles were coded into the unbiased category.

Table 2

| Articles from 2022 | Language Used | Biased or Unbiased |

| 2 | Only positive language | Unbiased |

| 3 | Mostly positive language | |

| 1 | Mostly negative language | |

| 0 | N/A | Biased |

V. Discussion

This research study aimed to examine Baltimore Sun framing of city crime coverage to determine whether it changed since the publication’s February 2022 public admission of biased reporting. The findings of the study suggest that the Baltimore Sun has changed its reporting, yet unexpected outcomes were also found when examining the relationship between the type of language used and type of reporting.

The results of this study are consistent with past research that examined how biased reporting and media framing of crime victims can lead to detrimental consequences for marginalized individuals or communities. A study emphasized how frames that rely on stereotypes to describe crime victims produces negative narratives and harms individuals (Arendt & Northup, 2015). As an example, a Baltimore Sun article from 2016 noted that a shooting victim was in an unsafe community with speculation of buying drugs (Wells, 2016). The story was framed to give more prominence to the victim visiting a suffering neighborhood where drugs are often sold than to the loss of a life. The slant of the 2016 story projected apathy and insensitivity and was coded “biased” in this study.

This analysis suggests that delivering stories using mainly positive language that is empathetic and constructed in a compassionate tone go hand-in-hand with unbiased reporting practices. After February 2022, four of the six articles relied on positive language in regard to marginalized individuals and communities to build crime stories. This suggests that the Baltimore Sun not only adhered to its promise to eliminate its biased reporting practices, but also changed the language it relied on for crime reporting. The results suggest that a relationship exists between the positive language used when reporting crimes involving marginalized individuals and communities and unbiased reporting practices by The Baltimore Sun.

The research revealed that from 2013 to 2021, almost 56% of the selected articles fell into the category of biased reporting. This means that more than half of the articles framed stories in a way that stereotyped or discriminated against marginalized groups or communities in Baltimore City when reporting crime. In contrast, none of the selected crime stories for the six months following the admission of biased reporting practices were coded as biased, indicating that reporters were following the promise to “do better” by the Editorial Board of the Baltimore Sun.

The findings also confirm that stories in 2022 framed crime news through a lens that demonstrated empathy and compassion for those that the newspaper has historically denounced. Language such as “solidarity and resilience” and “better social supports” is an example of narratives that build up individuals and communities. Overall, changing narratives is the key toward equitable reporting, and the evidence suggests that the Baltimore Sun is adhering to the promise of changing its reporting practices. This research highlights that the Sun is on the way to achieving the goal of using its influence to break down the barriers that have repeatedly held back individuals and communities.

VI. Conclusion

This study had three distinct research limitations. The first circumstance involved the researcher’s ability to be completely objective when analyzing the content in the crime articles. While journalists are thought to possess a natural reporting bias, the research coder of this study likely holds implicit biases that impact the data. If one or two additional researchers were used to examine the frames and code the articles as biased or unbiased, the study would be strengthened. Moreover, changing the methodology to include additional researchers safeguards against any subjective categorizing of the types of language used in the articles.

Another circumstance that limited the study also involved the analysis of the language in the articles. Because the methodology depended on one researcher to determine if the language used in the articles falls into a negative or positive tone toward marginalized individuals or communities, it limits the scope. However, developing a predetermined list of specific words and phrases deemed as positive or negative language to identify in the analyzed articles lessened subjectiveness. Approaching the investigations with a predetermined list that is streamlined for the researcher to adhere to would make for a more uniform and reliable study.

The final circumstance that limited the study involves the small sample size. Selecting several crime articles per month instead of one for analysis could potentially produce different results. The six articles examined from 2022 are considered a small sample size, and future research should expand the number of articles in the study.

Despite these limitations, the study’s findings provide evidence that articles after February 2022 framed crime story narratives with an unbiased angle that diffuses preexisting stereotypes of marginalized individuals and communities. By changing its long-standing institutional biases that fed societal inequity, the Sun’s use of positive language to frame crime news will expose readers to a more sympathetic view of marginalized populations. There is no doubt that the Baltimore Sun has shifted its frames away from biased reporting and perhaps readers will begin to recognize the structural causes of crime. In fact, the Sun’s influence may benefit Baltimore City residents by breaking down barriers and building a more inclusive community through its changing narratives.

Acknowledgements

Throughout the process of writing, Jessalynn Strauss was extremely influential and spent many days helping me review and revise each part of my article. I am extremely grateful for her guidance and support throughout this process and recommending my submission to the Elon Journal.

References

Abello, O. P. (2017, November 22). Baltimore Reckons With Its Legacy of Redlining. Next City. Retrieved from https://nextcity.org/urbanist-news/baltimore-reckons-legacy-redlining.

Alatzas, T. (2022, February 18). A note from The Baltimore Sun’s publisher and editor-in-chief. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/editorial/bs-ed-0220-apology-publisher-note-20220218-3abvrkq5afes3fhygpmdiwp4ri-story.html.

Anderson , J., & Fenton, J. (2018, September 28). 25-Year-old man fatally shot in South Baltimore; he had spoken out about armed robbery last year. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/crime/bs-md-ci-thursday-shooting-20180927-story.html.

Arendt , F., & Northup, T. (2015) . Effects of long-term exposure to news stereotypes on implicit and explicit attitudes. International Journal of Communication, 9, 2370–2390.

Badger, E. (2019, April 29). The long, painful and repetitive history of how Baltimore became Baltimore. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/04/29/the-long-painful-and-repetitive-history-of-how-baltimore-became-baltimore/.

Baltimore Police Department. Crime Stats | Baltimore Police Department. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.baltimorepolice.org/crime-stats.

Baltimore Sun Editorial Board. (2022, February 18). We are deeply and profoundly sorry: For decades, The Baltimore Sun promoted policies that oppressed Black Marylanders; we are working to make amends. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/editorial/bs-ed-0220-sun-racial-reckoning-apology-online-20220218-qp32uybk5bgqrcnd732aicrouu-story.html?gclid=Cj0KCQjwkOqZBhDNARIsAACsbfJIw7I-v1_VhOza4dlBRUVyvmekTrcS9FjV1jGBFAixipVlFGVGrlkaAqUZEALw_wcB.

Bloom, L. (2022, February 23). Crime In America: Study reveals the 10 most unsafe cities (it’s not where you think). Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/laurabegleybloom/2022/02/23/crime-in-america-study-reveals-the-10-most-dangerous-cities-its-not-where-you-think/?sh=43e156a87710.

Carlyle, K. E., Slater, M. D., & Chakroff, J. L. (2008). Newspaper coverage of intimate partner violence: Skewing representations of risk. Journal of Communication, 58(1), 168–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00379.x.

Comprehensive Master Plan. City of Baltimore: Department of Planning. (2006, May 25). Retrieved from https://planning.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/03%20History%20of%20Baltimore.pdf.

Coleman, R., & Thorson, E. (2002). The effects of news stories that put crime and violence into context: Testing the Public Health Model of Reporting. Journal of Health Communication, 7(5), 401–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730290001783.

D’Angelo, P. (2017). Framing: Media frames. The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0048.

Durr, K. D. (2011). Review of Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, by A. Pietila. The Journal of American History, 97(4), 1176–1176. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41509017.

Entman, R. (2007). Framing bias: Media in the distribution of power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

Entman, R. M., & Gross, K. A. (2008). Race to judgment: Stereotyping media and criminal defendants. Law and Contemporary Problems, 71(4), 93–133. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654685.

FBI. (2018, September 11). Crime clock. FBI. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/crime-clock#:~:text=The%20Crime%20Clock%20represents%20the,aggravated%20assault%20every%2039.0%20seconds.

Fenton, J., Costello, D., & Prudente, T. (2022, January 1). Baltimore tried new ways to stop the violence in 2021, but homicides and shootings remain frustratingly high and consistent. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/crime/bs-md-ci-cr-year-end-violence-20211231-nhiw6lykgzbofginwehe57cohq-story.html.

Fridkin, K., Wintersieck, A., Courey, J., & Thompson, J. (2017). Race and police brutality: The importance of media framing. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3394–3414.

Gramlich, J. (2022, October 31). Violent crime is a key midterm voting issue, but what does the data say? Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/10/31/violent-crime-is-a-key-midterm-voting-issue-but-what-does-the-data-say/.

Grove, M., Ogden, L., Pickett, S., Boone, C., Buckley, G., Locke, D. H., Lord, C., & Hall, B. (2017). The legacy effect: Understanding how segregation and environmental injustice unfold over time in Baltimore. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1365585.

Gurevich, L. (2022). Framing effect method in vaccination status discrimination research. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01299-x.

Hipp, J. R. (2010). A dynamic view of neighborhoods: The reciprocal relationship between crime and neighborhood structural characteristics. Social Problems, 57(2), 205–230. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2010.57.2.205.

Itkowitz, C. (2019, July 27). Trump attacks Rep. Cummings’s district, calling it a “disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-attacks-rep-cummingss-district-calling-it-a-disgusting-rat-and-rodent-infested-mess/2019/07/27/b93c89b2-b073-11e9-bc5c-e73b603e7f38_story.html.

Jones, C. P. (2002). Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon (1960-), 50(1/2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/4149999.

Kirk, D. S., & Laub, J. H. (2010). Neighborhood change and crime in the modern metropolis. Crime and Justice, 39(1), 441–502. https://doi.org/10.1086/652788.

Litovsky, Y. (2021). (Mis)perception of bias in print media: How depth of content evaluation affects the perception of hostile bias in an objective news report. PLOS ONE, 16(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251355.

Matthes, J. (2009). What’s in a frame? A content analysis of media framing studies in the world’s leading communication journals, 1990-2005. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900908600206.

Neckerman, K. M., & Torche, F. (2007). Inequality: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 335–357. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29737766.

Ott, B. L., & Aoki, E. (2002). The politics of negotiating public tragedy: Media framing of the Matthew Shepard murder. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 5(3), 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1353/rap.2002.0060.

Parham-Payne, W. (2014). The role of the media in the disparate response to gun violence in America. Journal of Black Studies, 45(8), 752–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934714555185.

Rothstein, R. (2015). From Ferguson to Baltimore: The fruits of government-sponsored segregation. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, 24(2), 205–210. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26408163.

Snidal, M., & Newman, S. (2022). Missed opportunity: The west Baltimore opportunity zones story. Cityscape, 24(1), 27–52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48657939.

Spinde, T., Jeggle, C., Haupt, M., Gaissmaier, W., & Giese, H. (2022). How do we raise media bias awareness effectively? Effects of visualizations to communicate bias. PLOS ONE, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266204.

TimesMachine. (1910, December 25) The New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1910/12/25/issue.html?zoom=16.2.

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Baltimore City, Maryland; United States. United States Census Bureau. (2021, July 1). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/baltimorecitymaryland,US/PST045221.

Wells, C. (2016, October 3). Man fatally shot in Southwest Baltimore. The Baltimore Sun.