Elon students and faculty are interacting in new ways this fall that blend online and in-person sessions to help promote health and safety while still providing an engaging learning experience.

During a typical semester, the vast majority of courses at Elon involve students and faculty interacting face-to-face and side-by-side in the classroom, having those personal connections that are more challenging to experience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

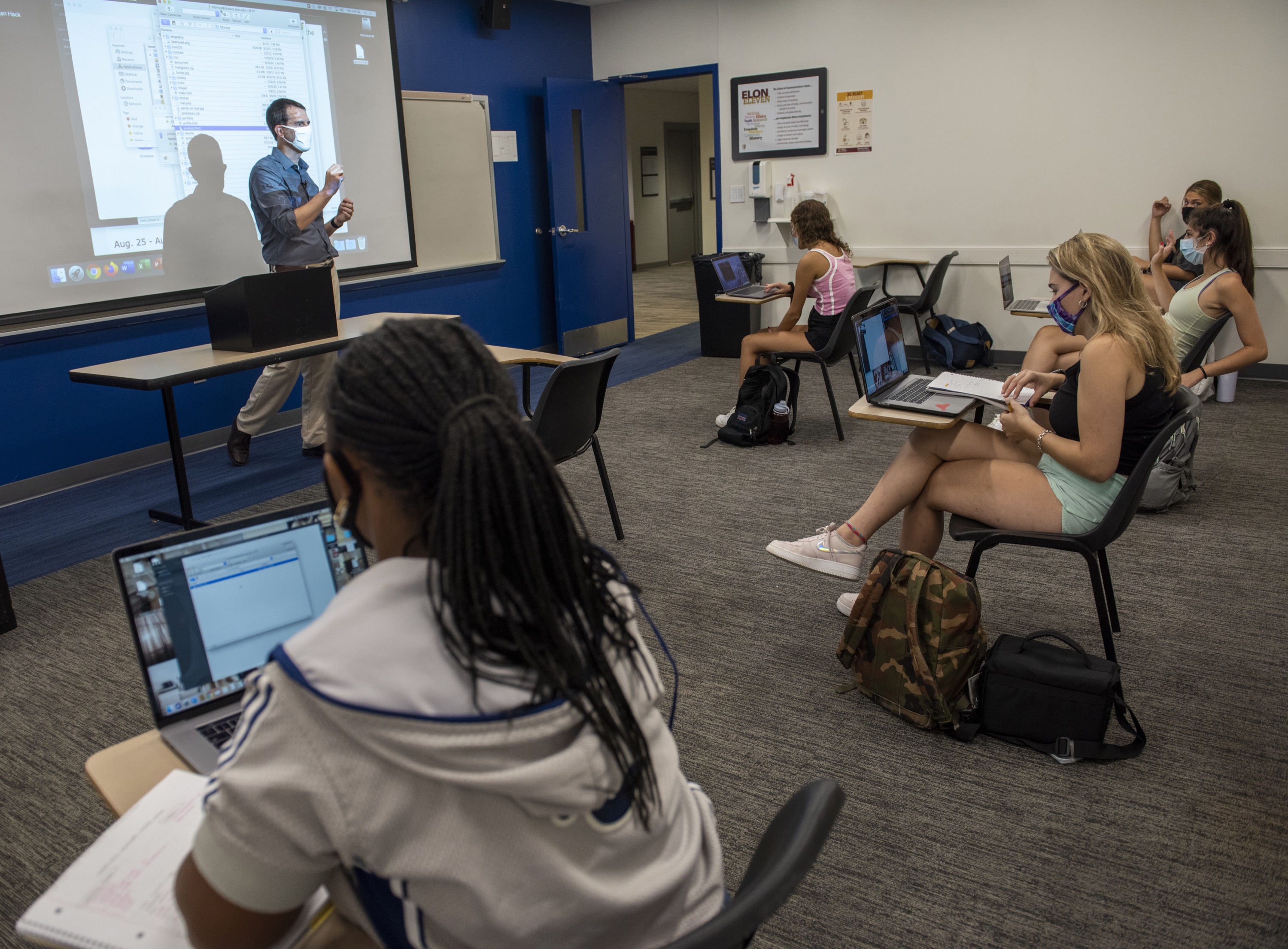

Among the steps taken this fall to promote a safe and healthy return to campus, many faculty members have adapted their courses to include both online and in-person elements in what’s a hybrid or blended approach to instruction. Once a rarity at Elon, hybrid classes are now the norm, with more than 70 percent of courses incorporating an online component in some way. Often, faculty members are integrating new technological tools into their courses with help from Teaching and Learning Technologies and a range of resources offered throughout the summer.

“A lot of faculty members have been thinking through what technological tools make the learning experience rich and help meet the learning outcomes,” said Deandra Little, assistant provost and director of the Center for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning. “That can mean using those tools to bring in-class and out of class students together.”

What exactly is a hybrid class?

At Elon, hybrid instruction is taking place in many forms. Most commonly, it can mean splitting a larger course in two, with half of the class attending each session and half connecting remotely at the same time. This synchronous approach allows all students to meet at the same time and provides for adequate physical distancing within the classroom. Everyone participating in the in-person session wears masks, and the number of desks in each classroom has been reduced, with the desks spaced out around the room.

Faculty members typically stream and record each session using a videoconferencing platform, and students rotate each session between being in class and connecting remotely. Often a student in class will serve as a connection between the two cohorts – relaying questions or comments from those connecting remotely.

While this is a common form that hybrid instruction can take, it’s certainly not the only one. Here’s a look at three Elon faculty members and the different models they have adopted to best fit their classes and their content. While these models were adopted in response to the pandemic, all three faculty members say there are elements to hybrid instruction that they may continue to use even once the extensive health and safety measures are no longer required.

Margarita Kaprielyan, assistant professor of finance

The “Real Estate Finance” and “Financial Modeling with Excel” courses that Assistant Professor Margarita Kaprielyan teaches are typically technology-heavy, as both rely upon popular Microsoft Office program Excel. Both classes are large enough that Kaprielyan needed to split each in two, with half of the class attending each session and the other half working independently outside the classroom.

A big change for Kaprielyan was to adapt how she and her students were using their time in class and outside the classroom. She adopted a “flipped” classroom model that has students watching videos of Kaprielyan walking them through the various concepts and techniques when they are not in the classroom, and then using the time in class to work collaboratively and apply the material to practical use.

The model allows students the opportunity more time to digest concepts at their own pace outside of class before coming to class to apply them, Kaprielyan said. “One of the challenges I found teaching technical courses is that the pace is really important,” she said. “They can follow along with me in the videos, and then rewind depending upon how well they are grasping the ideas. It makes it more accessible.”

While they are working their way through the videos outside of class, they are filling out Excel workbooks that to help record their progress. At the next in-person class session, they submit the workbook so that Kaprielyan can make sure they have the foundational knowledge they will need to move forward in class with the practical application.

Though in person inside the classroom, Kaprielyan and her students are logged into the videoconferencing platform Zoom, which allows them to essentially huddle and discuss what they are working on at the same time in a breakout room while maintaining physical distancing. Having the class on Zoom also allows the few students who are learning remotely this semester to engage with the class, she said.

Mark Enfield, associate professor of education

The two courses Associate Professor Mark Enfield is teaching this fall include one that is new to him and one that is new to the School of Education curriculum, and he has implemented a similar team-based model for both. Since they are both new courses, Enfield said he felt more freedom to structure them differently since he was building them from the ground up. That structure was born out of necessity as it related to keeping in-person meetings small, as well as just what made sense for the content.

“Since I don’t have any ‘I’ve always dones’ for these courses, I was able to say, ‘I’ll do what I need,’” Enfield said.

In the two courses — “Foundations of 21st Century Teaching” and “Science for Elementary Teachers” — the students are grouped into two clusters, and then each cluster was divided into multiple teams with four students in each team. During each in-person class session, one cluster attends the first half of the session, and the other cluster attends the second half.

Enfield started the semester giving students a set of expectations, the first of which is that each student will care for each other and help make sure their team members are safe, secure and healthy, as well as challenging and supporting each other academically. “I thought this was a good way to reinforce some of the university’s Ready & Resilient ideas,” Enfield said.

Each team is tasked with meeting either virtually or in person for about an hour and a half each week, ideally spread across two sessions. In these sessions, they undertake a project assigned to them for the week. For instance, teams in the Foundations class were provided a set of children’s book that focused on topics of social justice and equity. Teams read and discuss the books to consider how the stories inform their thinking about classroom management and culturally sustaining pedagogy. The team members annotate their meetings in a Google Doc that is shared with Enfield, with those annotations completed and submitted at the end of the week.

Each cluster also meets in person with Enfield in the classroom. For the Science for Elementary Teachers course, students use the time in the classroom to conduct scientific investigations focused on understanding science concepts in the elementary grades. Working in teams outside of class, the team spends 45 minutes collecting data and sifting through data, look for patterns and discuss the different concepts at work. In class, the clusters of two teams meet to compare results and develop clearer explanations of phenomena in order to understand science concepts and ideas.

“One of the benefits of this is they are going to actually need to, in their teams, reconcile a set of data,” Enfield said.

Enfield said this model, which he will re-examine midway through the semester with his students to gauge its effectiveness, allows him to be more engaged with the work students are undertaking outside the classroom and also create time for collaboration while together inside the classroom. It also places a lot of responsibility on the individual students, and on the teams.

Enfield has focused on his students taking a more active role in how they learn this semester. “I’m expecting them to be bigger participants in our collective work,” Enfield said. “As a class, they need to care for one another and I’m depending on them to help make the semester work. I’m putting them more in charge of some of their learning.”

Kelly Furnas, lecturer in journalism

Lecturer Kelly Furnas has also pursued a flipped classroom model for his Web and Mobile Communications course that is focused on web development. That meant Furnas spent much of his summer recording videos of his lectures. Students watch those videos outside of class and then come to class to work on their assignments and to get individualized help.

In the video lectures, Furnas blended screen captures with presentations and incorporated video and animation. Many include interactive questions and denote chapters for easy review. Furnas has a custom of kicking off each class session with music, and so he has included that element in the recorded lectures as well. “It was just one way to try to replicate the classroom at some level,” he said.

The course meets on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and students are assigned cohorts that meet in person either at the beginning or end of the class period. “That way, they can come into class with their questions or problems raised by the lectures, and we can work on them together,” Furnas said.

During each class session, students can connect via Zoom, with the Zoom conference displayed on the screen in the front of the class. Students not in the classroom are welcome to join in as well.

In the past, Furnas would move around the room from student to student to offer personalized feedback, often standing over their shoulders or even using their computers. The Zoom conference allows for those kinds of personal discussions to take place while physically distanced. It also helps relay advice to multiple students who may be confronted with the same problem, Furnas said. “They can share their screens in the front of the room, with the added benefit that all students in the room can see common problems and solutions,” Furnas said. “I mic myself up so that students who video conference in can hear me even as I walk around the room.”

The adapted approach means Furnas spends more time setting up the classroom for each session. “Gone are the days, I suppose, of strolling into a classroom a couple of minutes before a lecture,” Furnas said. “We have to think proactively about how much technological set-up time is involved with each and every day of class.”