How do we assess?

How Do We Assess? Equity-Minded Assessment

Assessment is an integral part of the learning process. The purpose of assessment is to ascertain the degree to which students understand our course content and perform the skills that we’ve taught.

Well-designed assessments enhance students’ learning – by guiding their efforts in an appropriate direction and by raising their awareness both of what they understand and where they might improve. Seeing evidence of what students understand and don’t understand also helps instructors refine their teaching methods.

For instructors aiming for equity and inclusion, assessment poses some challenges. The good news is that there are targeted strategies we can use to address them.

Some Challenges

Students come into our courses with different educational backgrounds and prior knowledge.

What they learned before they enter our classrooms affects students’ performances, advantaging some and disadvantaging others. It’s difficult for instructors to know whether a student’s performance on an assessment reflects what she has learned in the course or what she already knew.

Education scholars refer to the detrimental effects of the “hidden curriculum,” which consists of many “tacit rules in a formal educational context that insiders consider to be natural and universal.” Research on first-generation students shows that those with prior knowledge of those tacit rules are more prepared to succeed (Jaschik).

Unfortunately, instructors might unintentionally use assessments that reward some students’ prior experience in performing a specific kind of work (e.g., argument-based essays) or their skill in test-taking rather than solely understanding of content. Along with content, some assessments measure “construct-irrelevant” factors, such as motor coordination (handwriting or typing), attention, time management, the ability to work quickly under pressure (UDL on campus).

Individual variability is the norm in our classes. As CAST observes, an international student whose native language is not English will face challenges in writing a long essay, especially if he can’t access a dictionary or if there is a time limit, and a student with Attention Deficit Disorder may have challenges with working memory. The obstacles that individual students face make it difficult to know the degree to which they have comprehended course material. “Assessment data can contain a significant amount of ‘noise’ if assessments are measuring the student’s ability to navigate the test, assignment, or course rather than the actual material” (Montenegro & Jankowski).

Instructors have biases that can affect assessment.

Faculty have good intentions; we want to be fair and consistently apply appropriate, discipline-based standards. However, psychologists tell us that we all have unconscious biases about different kinds of people that may affect our ability to evaluate student work fairly and consistently. In addition, confirmation bias may lead instructors to evaluate work in a manner that that confirms their existing views of individual students. For example, one might unconsciously expect a student who makes smart comments in class to perform well on an exam or essay and therefore award that student a few more points on borderline work. Conversely, an instructor might not fully appreciate the work of a student perceived as quiet or less capable during class or earlier in the semester (Steinke & Fitch).

It’s difficult to design effective assessments that students and faculty have confidence in.

Many instructors have spoken with a smart and hard-working student who was frustrated because she didn’t demonstrate all that she understood on an essay, exam, or project. Some students, aware of public discussion about biases and problems with standardized tests, wonder about whether instructors and systems of assessment are fair. Indeed, some faculty themselves aren’t confident that they’ve designed assessments that effectively measure higher-order thinking, align with the content they’ve taught, and give all hard-working students a fair chance.

Most forms of assessment have limitations. Some traditional tests of facts are easy to grade but measure lower-order thinking or allow for guessing. Open-ended questions are better suited for assessing higher-order thinking and depth of understanding, but they take longer to grade and are more difficult to grade consistently. Whatever the format used, students are often confused by specific prompts, directions, or expert jargon, which we may learn too late (Winkelmes).

While it would be convenient to ignore the occasional discontented student or see students as being overly focused on grades, students’ performance on assessments may have significant implications. Grades may affect whether students decide to continue in a field or will have access to future opportunities such as undergraduate research mentoring, scholarships, or acceptance to post-graduate programs. Assessments that are poorly designed, unfair, or even perceived as unfair undermine the trust and sense of belonging that are critical for positive learning experiences.

Questions Instructors Face

Since Elon instructors have the responsibility to assess student performance and assign grades, how can we do it with integrity?

- How do we design assessments/assignments – and teach – so that all students have a chance to succeed, not just those who entered our course with educational advantages?

- How do we design assessments/assignments that are meaningful, assess what we want them to, and help all our students learn?

- How do we design a course grading scheme that gives students a chance to grow and learn from their previous work and mistakes?

- How do we ensure consistency and minimize the effects of our biases when evaluating students’ work?

What Instructors Can Do

Equity-minded assessment starts with instructors’ willingness to closely examine their assumptions and practices. One can do that in partnership with CATL and other colleagues who are concerned about maximizing the potential and learning of all students.

It’s important to be clear about our specific learning goals and give close and analytic attention to students’ work. Understanding students’ experiences and perspectives – their diverse strengths, motivations, and barriers – is also helpful. “One of the easiest ways to check your assumptions is to actively involve students in the process of assessment,” observe Montenegro and Jankowski.

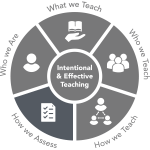

Please follow the links below to find specific recommendation from DEI research in four areas:

The kinds of assessments we use

The course grading scheme

Teaching strategies to prepare students for success

Equitable grading and feedback practices

Works Cited & Resources

CAST. UDL and Assessment. Universal Design for Higher Education.

Georgetown University Center for New Designs in Learning & Scholarship. Inclusive Pedagogy Toolkit: Assessment.

Jaschik, Scott. “The Hidden Curriculum.” Inside Higher Education, January 19, 2021.

Montenegro, E., & Jankowski, N. A. A new decade for assessment: Embedding equity into assessment praxis. University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment, 2020.

Steinke, Pamela, and Fitch, Peggy. Minimizing Bias When Assessing Student Work. (2017). Research and Practice in Assessment 12, 87-95)

Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. “Benefits (some unexpected) of Transparently Designed Assignments.” National Teaching and Learning Forum 24, 4: May 2015.